When Companionship Became a Community – Part 2

From first principles to floor plans: practicing suhba (companionship) here and now.

In the first paper, we stood in the warmth of the Prophet’s ﷺ city. We learned the grammar that turned companionship into community: mu’akha (covenant of brotherhood), ithar (altruism), qana’ah (contentment), and attention that felt like shelter. We saw that culture is not an event, but a climate formed by repeated acts of mercy—each one braided with sabr (patience) and tawakkul (trust in Allah).

This second paper asks a practical question: How do we translate those first principles into a world whose architecture often resists touch? Streets curve into cul‑de‑sacs, calendars move faster than hearts, and our rooms risk becoming efficient but aloof. Our answer cannot be nostalgia. It must be niyyah (intention) made visible—through redesigns of space, schedule, and reflex that make mercy plausible again.

What follows is a mirror and then a map. We will face the habits our age has taught us, begin again with why, cultivate a culture that lingers after the program ends, and practice the interior weather—commitment, vulnerability, and initiative—that makes belonging durable. We will move slowly, with sabr and tawakkul, trusting that Allah adds what sincerity begins.

“What has been cut apart cannot be glued back together. Abandon all hope of totality, future as well as past, you who enter the world of fluid modernity.” –Zygmunt Bauman1

The Modern Mirror

Formation asks for a world where people can touch each other’s lives without an appointment. Yet much of our world resists touch. Streets curve into cul‑de‑sacs that keep us from wandering. Garage doors seal us in and out like airlocks. Apartment towers offer everything but a reason to knock next door. We did not always choose loneliness; often, we inherited a design that trains our habits. It becomes normal to pass one another at a pace that forbids interruption, to live adjacent without ever quite belonging.

Scholars have been naming this thinning for years. Robert D. Putnam traced the slow unraveling of civic life—how the clubs, leagues, and neighborhood rituals that once stitched strangers into neighbors have frayed—and he called the ache by its image: Bowling Alone.2 Zygmunt Bauman described how modern bonds turn liquid—light enough to carry, easy enough to drop—so that commitment feels like a hazard rather than a home.3 Their diagnoses are not revelations, but they help explain why the heart can feel homeless in a house: our built environment catechizes us into privacy, mobility, and exit.

Public health has caught up to what imams and counselors have heard for years in quiet rooms. The Surgeon General of the United States speaks of loneliness and isolation not only as sadness but as risk: higher rates of heart disease and stroke, depression and anxiety, and early mortality. The advisory’s remedy sounds familiar to anyone who has sat with the Prophet’s ﷺ city: rebuild relationships, recover meaningful purpose, and renew service that stretches across institutions and neighborhoods.4

Our mosques and organizations are not immune to the prevailing design trends. We can become efficient but aloof—strong at programming, thin at presence. We polish stages and forget the porches. We count attendance and those who left early. We perfect the run‑of‑show and neglect the slow‑of‑soul. People come, listen, and leave with the same ache they carried in. They needed a circle; we offered a schedule. They needed a companion; we gave them a calendar invitation. It is not malice. It is a drift toward what is measurable over what is meaningful.

Repentance, in this register, looks like redesign. If architecture teaches, then floor plans are a form of moral language. Build thresholds that are easy to cross. Choose rooms that default to circles, not rows, when the purpose is suhba. Place chairs so that eyes can meet without strain. Leave margins in the program for conversation that wanders into care. Budget for meals as if barakah were a line item, because it is. And create gentle ways for people to be seen without spectacle—sign‑ups that translate into real visits, text threads that become dinners, foyers that feel like invitations rather than corridors.

None of this denies the speed of our age; it chooses to set a counter‑rhythm. The Prophet ﷺ did not build a city by accelerating everyone; he built it by humanizing time—by welcoming interruption as a site of obedience, by turning attention into shelter, by expecting Allah to add what sincerity begins. Our mirror is honest: we have built for convenience and called it community. Our hope is practical: we can build for communion again. “The believers are but brothers,” the Quran reminds, and then commands us to reconcile and to be mindful so that mercy may descend.5 The path back is not dramatic. It is a series of small redesigns—of rooms, of calendars, of reflexes—until belonging stops feeling like an exception and starts feeling like the air.

“There are only two ways to influence human behavior: you can manipulate it, or you can inspire it.” –Simon Sinek6

Begin with Why

Before we ask what hospitality is—or how to do it—we must decide why we are doing it. Writer Simon Sinek frames it this way: people do not commit to what you do; they commit to why you do it.7 When the why is clear, the how stops feeling frantic, and the what begins to cohere. Our why is not branding; it is worship: to help people feel held by one another and drawn nearer to Allah, so that rooms become conduits of barakah and hearts learn trust. The Prophet ﷺ gave us the grammar for this: “Actions are only by intentions.”8 Say the intention first, or we will mistake activity for meaning.

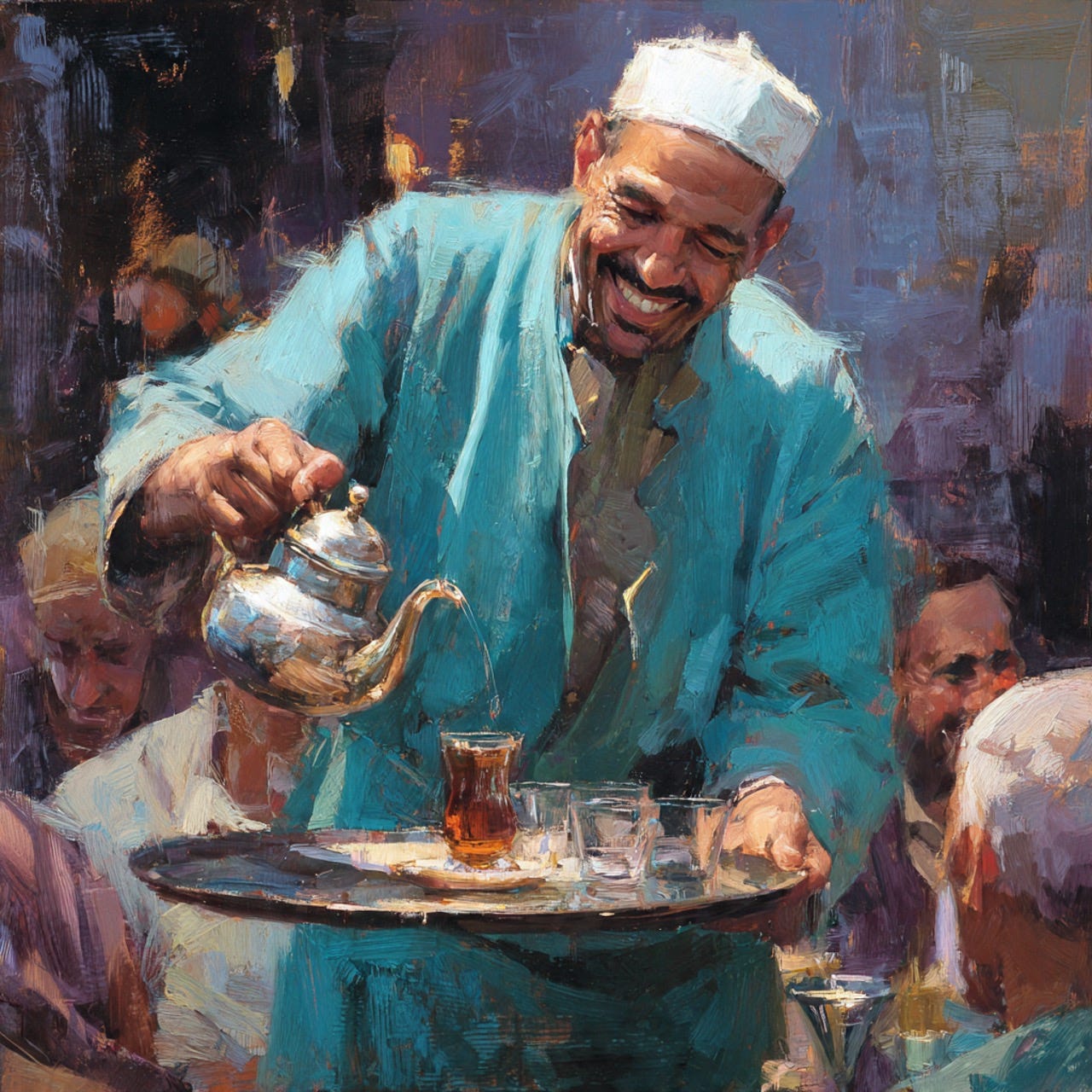

Once the intention is spoken, the room changes. You can feel it in the way volunteers gather before anyone arrives. A short supplication settles the air. There is no hurry to impress, only a shared willingness to notice. Chairs are not placed to face a stage but to face each other, as if to say, “You matter more than the program.” Someone has prepared food that can stretch without embarrassment. Another has decided to wait by the door, not as a greeter with a script but as a host with time. The details are the same as any event—sign‑in, tea, seating—but the texture is different. Attention begins to preach long before a word is said.

When people enter, hospitality takes the shape of presence. The Prophet ﷺ turned his whole body toward the one who spoke; that posture is a school of its own. In our setting, it looks like slowing to learn a name without making the moment heavy, leaving a little silence in the conversation so meaning can breathe, allowing the shy to belong without performance. The food is modest but elastic, because the intention has already trained the room to expect increase. What could have been a schedule becomes a circle. What could have been a talk becomes a meeting place for lives.

Afterward, the intention keeps working. The measure of the night is not applause or photographs. It is whether someone who was on the edge now has a way back into the middle. A non-transactional message is sent. A visit is made without ceremony. The host remembers the burden named in passing and makes quiet room for it in the coming week. Budgets, calendars, and floor plans begin to bend around these minor compliances. Over time, they become a culture that can carry weight.

Hospitality, then, is not the why; it is how love keeps faith with the why. When we begin with intention, details turn into devotion. The room becomes plausible evidence of Allah’s nearness. People leave with a warmth that outlasts the evening, and the work continues in the ordinary—at a doorway, at a table, on a sidewalk—where sincerity is felt without being announced.

“We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” –Will Durant9

Culture That Lingers

Culture is not a checklist of universal practices, and building suhba is not a one‑size‑fits‑all formula. In hospitality, Will Guidara argues that truly human service must be tailored to the particular guest—“one size fits one”—an insight that travels well into sacred community.10 The Messenger of Allah ﷺ embodied this long before our manuals: he adjusted his way to the person in front of him without compromising principle—praising even a humble table with, “What an excellent condiment vinegar is,” so a poor host would feel honored rather than exposed.11

Culture is atmosphere, not architecture. It is what lingers once the program ends: the warmth in the room after the lamp is blown out, the scent that clings to your clothes when you leave a beloved house. In Madinah, that atmosphere came from repeated gestures of mercy more than from announced initiatives—the tone that made people brave enough to ask questions and gentle enough to hear difficult answers.12 Culture is the unspoken grammar of a community; you do not see it on a schedule, but you feel it in the pauses and the aftercare.

Such a culture does not appear by accident; it is cultivated on purpose. The Prophet ﷺ taught us to begin everything with niyyah: “Actions are only by intentions,” lest we mistake activity for meaning. He also taught us to trust small, faithful repetitions: “The most beloved deeds to Allah are those done consistently, even if they are few”—because what we repeat with sincerity slowly becomes who we are. Over time, intention plus repetition hardens into instinct; the community begins to choose mercy before metrics because mercy has become reflex.

When these threads hold, a prophetic culture begins to teach without speaking. People find themselves acting with gentleness when no one is watching; a newcomer is remembered the next day without being assigned; a burden mentioned in passing is carried as if it were one’s own. That is the test: not how loudly we declare our values, but whether their fragrance remains after the microphones are silent. And because the atmosphere does not sustain itself, it requires an inner grammar that keeps the air warm when memories fade. In Madinah, that grammar moved like three quiet vows shaping instinct from the inside out: a resolve to stay (commitment), a courage to be seen and to see (vulnerability), and a readiness to move first (initiative). What follows is not a new program, but the interior weather that makes any culture of suhba durable.

“Vulnerability is the birthplace of love, belonging, joy, courage, empathy, and creativity.” — Brené Brown13

The Interior Weather

If culture is the air a community breathes, these three habits are the currents that keep it alive. They are not techniques; they are ways of being that the Prophet ﷺ nurtured until they felt native to the soul.

Commitment—staying long enough for love to work.

Madinah held because people did not treat each other as experiments. They tied their lives with covenantal seriousness and learned to repair rather than replace. Revelation names the bond and makes it an instruction: “The believers are but brothers; so make peace between your brothers, and be mindful of Allah so that you may receive mercy.”14 Commitment is what gives culture a memory; without it, every circle becomes a revolving door. In our present, commitment looks like refusing to let conflict do the scheduling, choosing to return to the table after hard words, and measuring success by who is still with us a year from now.

Vulnerability—letting truth have a body.

A city can be polite and still be spiritually mute. The Prophet’s ﷺ people learned a braver courtesy: to be truthful without spectacle and receptive without defensiveness. “O you who believe, be mindful of Allah and be with the truthful.”15 Vulnerability is not performance; it is proximity with the guards down enough for nasiha to land and for correction to heal. It sounds like, “I was wrong,” spoken early, and “I am with you,” spoken when someone expects to be left. In such air, purpose ceases to be a brand and becomes a shared prayer.

Initiative—love that moves first.

If everyone waits to be invited, no one is welcomed. The Prophet ﷺ coached a reflex that made welcome feel inevitable: “The food for two is sufficient for three, and the food of three is sufficient for four.” He widened tables for the poor of Ahlus-Suffah,16 directing households to add a guest beyond what seemed possible. Initiative is not a hustle ethic; it is khidmah as instinct—sending the message before it is asked for, showing up before the calendar insists, setting one more place because trust has taught you that Allah adds what love begins.

Held together, these three are the interior weather of belonging. They keep culture from becoming ambiance without a backbone. Commitment keeps us in the room; vulnerability makes the room truthful; initiative keeps the room generous. In that climate, barakah becomes plausible again—the room feels larger than its square footage, the conversation lingers beyond its minutes, and the circle remembers the one who almost slipped away.

“I feel so strongly that deep and simple is far more essential than shallow and complex.” –Fred Rogers17

Circles That Outlive Us

Return, for a moment, to that city the Prophet ﷺ warmed. Picture the women of the Ansar asking brave questions; the Muhajirun learning a new market by morning; a poor man from the Ahlus-Suffah eating because someone at the edge waved him into the center. None of that required spectacle. All of it needed sincerity—the kind that expects Allah to add what we cannot.

We will not build another Madinah, and we are not asked to. We are asked to build what made it holy: presence, care, and mercy offered for Allah’s sake. Public‑health language now names the medicine with data; Revelation names it with kinship: “They give preference to others even when they themselves are in need.”18 Between those two languages lies our path—relationships to keep, purposes to share, services to render.

So I begin where I am, seeking first principles rather than replicas. A shared meal that stretches. A visit that interrupts my schedule and becomes the memory of the week. A message that says, “I was thinking of you,” not because there is news, but because love needs rehearsal. I will practice turning my whole body toward whoever speaks. I will ask Allah for barakah and plan the dishes. I will start again next week.

O Allah, make us people of niyyah and suhba. Teach us to stay when staying is hard, to open our hearts enough to be known and to know others, and to take the first step in love before being asked. Let our rooms be warmer than their walls, and our programs a means of nurturing hearts, not measuring them. Fold us into circles of mercy that outlast our names. Clothe us in sabr and fill us with tawakkul, and make every small act a door to Your nearness. And when we are gone, let a quiet sweetness remain—enough to remind those who come after that we once tried to be together, for You. Ameen!

Ultimately, with Allah is all success.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000. 22.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Bauman, Liquid Modernity, 2000.

Office of the Surgeon General. Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community. Washington, DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2023.

Quran 49:10.

Sinek, Simon. Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. New York: Portfolio, 2009. 39.

Ibid., 41.

Durant, Will. The Story of Philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1926. 87.

Guidara, Will. Unreasonable Hospitality: The Remarkable Power of Giving People More Than They Expect. New York: Optimism Press, 2022. 17.

Quran 3:159.

Brown, Brené. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. New York: Avery, 2015. 33–34.

Quran 49:10.

Quran 9:119.

Ahlus-Suffah (“people of the shaded platform”) were a group of poor Muslims, who were given permission by the Prophet Muḥammad to live in a corner of the Madina mosque. They were “guests of Islam” with no families or means; the Prophet ﷺ routinely directed that they be fed and shared gifts with them. See “Ahl al-Suffa .” The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Encyclopedia.com. (October 6, 2025). https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/ahl-al-suffa and Sahih al-Bukhari 6452.

Wagner, Benjamin, and Christopher Wagner, dirs. Mister Rogers & Me. New York: Wagner Brothers, 2010. Broadcast on PBS, 2012.

Quran 59:9.

Thank you. I’ve often reflected on how mosque expansions carry both joy and quiet loss. When a musalla grows into a masjid, there’s excitement and movement — new rooms, new faces — but something subtle can slip away. In smaller spaces, brotherhood and sisterhood happen almost by proximity; we see and know one another. In larger spaces, that nearness requires intention. Without it, the walls widen, but the hearts drift.

AA would love to read some of your historical articles on Domestic Abuse in the Muslim community. Please guide. Chaplain NuR Moebius Fitzpatrick ##Retired