When Companionship Became a Community – Part 1

Suhba (companionship) as formation: the Prophetic architecture of belonging.

Late at night, the house quiets, and the ache begins its small conversations. The screen glows. Names move like lanterns across a dark river. We can reach anyone and still not feel reached. This is more than a social hunger; it is a spiritual wound—an absence of mercy moving through the ordinary hours, a thinning of breath where remembrance should be.

Madinah itself did not teach anyone anything. It was the Messenger of Allah ﷺ who taught—who turned rooms into schools of mercy and hunger into trust. By his presence, attention, and prayer, he disciplined love until it became a way of life. He gathered the displaced and the rooted, the cautious and the warm, and taught each to make space for the other. He trained hearts to sit, to listen, to stretch a small meal and expect barakah (blessing), to live sabr (patience) and tawakkul (trust in Allah), not as ideas but as muscle. The city warmed because he was there; the climate changed because revelation was embodied in him.

This reflection continues a quiet thread from “Friendship: Deep, Not Wide”—moving from the scale of one faithful bond to the architecture of a city shaped by revelation.

I am not trying to recreate a museum of their streets. I am trying to walk with them long enough to learn first principles I can carry into a world they could not have imagined. I want to test what in their reality is transferable across centuries: ikhlas (sincerity) before strategy, niyyah (intention) before logistics, mu’akha (covenant of brotherhood) before contract, hospitality before programming, presence before performance, boundaries that protect dignity, rhythms that make mercy habitual. They were the best generation, and I approach them as a student who expects to be changed—because the Prophet ﷺ said, “The best people are those living in my generation, then those who will follow them, then those who will follow the latter.”1 It’s in their practices that I search for foundations, not replicas; for truths sturdy enough to hold in cul‑de‑sacs and high‑rises, under fluorescent lights and phone screens alike, wherever our era’s darkness asks to be met.

“You will not enter the Garden until you believe, and you will not believe until you love one another. Shall I tell you something which, if you do it, you will love one another? Spread peace among yourselves.”2 –Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

Two Histories, One Tapestry

Sayyida Aisha—may Allah be pleased with her—named something native to Madinah: modesty that did not silence learning. “How excellent are the women of the Ansar. Their modesty did not prevent them from learning their religion.”3 That single praise opens a sociocultural picture: an oasis town of palm groves and irrigation channels, clustered kin and ready doors. Questions there were part of reverence; neighborliness had a grammar formed by shared tools, shared time, and harvests that required one another.

Even the economy sounded like a garden. The Ansar were farmers; many of the Muhajirun (Emigrants) entered share‑cropping arrangements in the Ansar’s groves—reciprocity turning soil into school.4 Their civic memory also carried the ache of civil war—Aws and Khazraj (the two major Arab tribes) bleeding one another until the Day of Buʿāth, just before the Hijrah. Exhaustion made the city ready for a teacher who could turn rivals into kin.5

It was a mosaic as well—Muslim Emigrants, Ansar hosts, and established Jewish clans with their own law and land. Early on, the Prophet ﷺ set down a civic covenant—what later sources call the Sahifat al‑Madīnah—naming the believers one ummah (community) while binding neighbors to mutual obligation across difference. It did not erase sociocultural lines; it moralized them into responsibility.6 He established a market to guard fairness and make honesty public, so trade itself became a daily school for trust.7

Across from this stood the Makkan cohort—formed not by orchards but by pressure.8 They endured the long boycott in the valley of Abī Ṭālib, a schooling in hunger and vigilance.9 Khabbāb ibn al‑Aratt recalled sitting with the Prophet ﷺ by the Kaʿbah and pleading for relief, a memory that tells the temperature of those years.10 Revelation itself names their condition: “As for those who emigrated in ˹the cause of˺ Allah after being persecuted…”;11 “Remember when you had been vastly outnumbered and oppressed in the land…”12

Set side by side, these are formations, not essences. Madinah’s neighborly candor and Makkah’s disciplined caution met in the same house. The Prophet ﷺ did not flatten them; he tuned them—pairing Emigrants with Helpers in mu’akha, honoring the Ansar’s generosity while refining it, honoring the Muhajirun’s reserve while warming it.13 He taught the city to love the Ansar as a sign of faith, not of faction.14 From the Prophet’s ﷺ time onward, real communities have been tapestries—threads dyed by different histories, woven by a single intention, held together by sincerity. Our task is not to make everyone alike; it is to welcome what each history teaches and let revelation braid those differences into one fabric of belonging.

Love That Pays the Cost

When the Prophet ﷺ arrived in Madinah, he paired the displaced with the rooted—mu’akha. It was not charity but covenant, which is to say commitment that outlives mood. The classic scene: Saʿd ibn al‑Rabīʿ offered half his wealth to ʿAbd al‑Raḥmān ibn ʿAwf; ʿAbd al‑Raḥmān answered with gratitude and dignity: “May Allah bless your family and your wealth—show me the market.” Two virtues face one another across a threshold: ithar (altruism) and qana’ah (contentment). Both are love paying a cost, neither is theatrical. This is what friendship—deep, not wide—looks like when it scales: covenant first, convenience second.

Revelation named this posture a sign of success: “They give ˹the emigrants˺ preference over themselves even though they may be in need.”15 That verse descended into scarcity, not surplus. The Ansar did not distribute leftovers; they reallocated trust, believing that what left the hand would return to the heart as barakah.

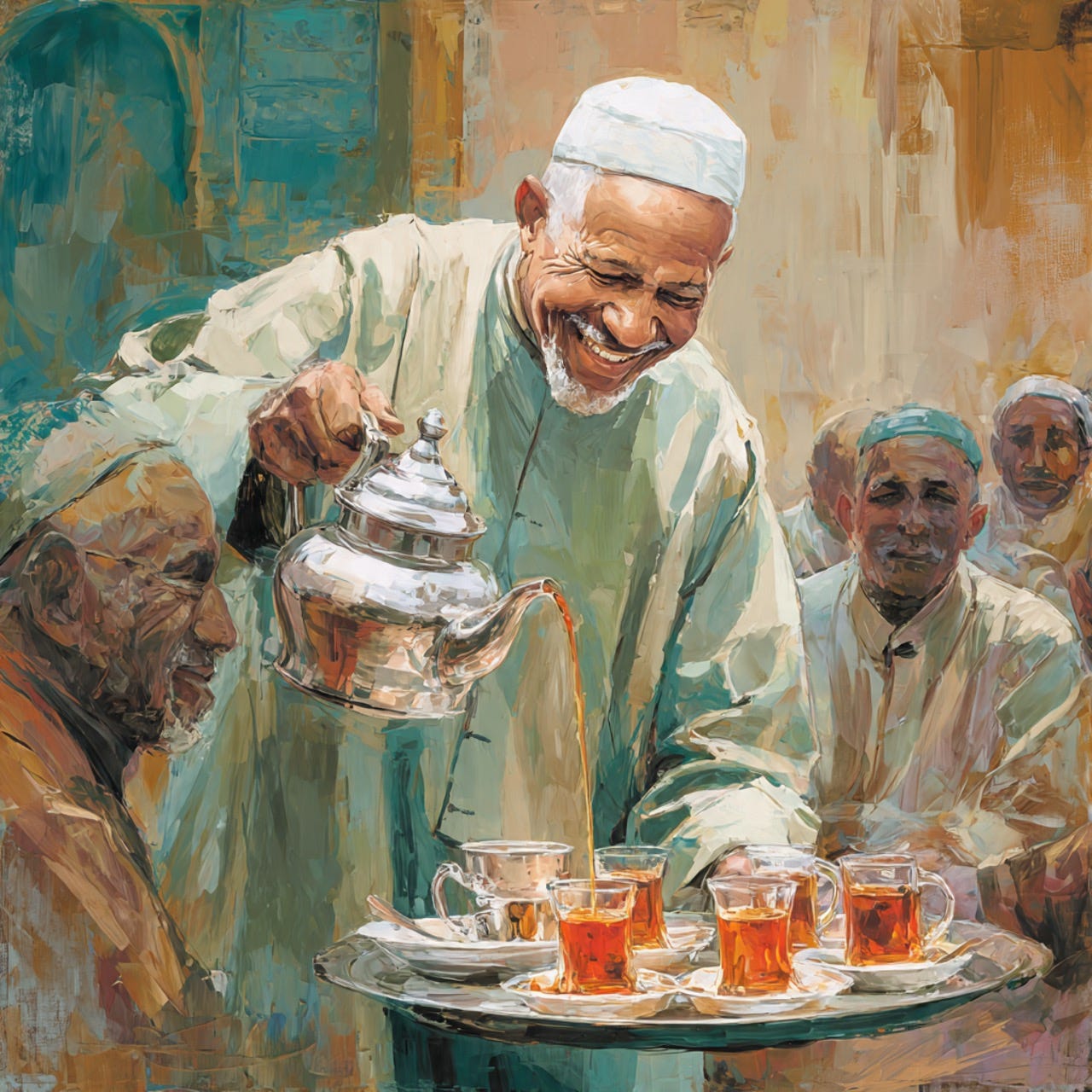

The Prophet ﷺ coached this sacrificial reflex through ordinary choreography. “The food for two is sufficient for three, and the food of three is sufficient for four,” he said—training a city to expect increase where love adds places. In another report: “Food for one suffices two; food for two suffices four; food for four suffices eight.”16 He multiplied invitations for the poor of the Suffah17: “Whoever has food enough for two, let him take a third from among them; whoever has food for four, let him take a fifth or a sixth.”18 And he set the inner law of such giving: “None of you truly believes until he loves for his brother what he loves for himself.”19

This is the transferable second principle for us: in community, we must sacrifice for one another from a place of love. In our world, that sacrifice often looks like time and attention rather than loaves and rooms: changing a schedule to accompany someone to an appointment, doing unseen labor to make a space feel warm, carrying a reputation when a friend stumbles so that shame does not finish what sin began. The fuel is tawakkul and sabr. We give from what feels like not enough, believing the increase will come—even if it is not measurable.

An Ecosystem of Mercy

The day Sa’d b. Al-Rabi’ offered half his wealth to Abdul-Rahman b. ‘Awf and heard, “May Allah bless your family and your wealth—show me the market,” is not only a story of two men being noble; it is a window into how the city breathed. The Prophet ﷺ cultivated not isolated acts but a circulating life: giving, receiving, advising, and correcting moved like blood through a body. In that pulse, ithar met qana’ah, and trust kept the currents from stagnating.

Revelation sketched this as a social watershed: “The believers, both men and women, are guardians of one another. They encourage good and forbid evil, establish prayer and pay alms-tax, and obey Allah and His Messenger.”20 The ethic is widened elsewhere: “Cooperate with one another in goodness and righteousness, and do not cooperate in sin and transgression.”21 This is the Prophet’s ﷺ ecosystem: mutual guardianship, shared duties, reciprocal care.

He taught us to imagine the whole with two images. First, “A believer to another believer is like a building whose different parts reinforce one another,” and he interlaced his fingers to show the fit—complementarity as architecture.22 Second, “The believers, in their mutual love, mercy, and compassion, are like a single body; when one limb suffers, the whole responds with wakefulness and fever”—responsiveness as physiology.23

Seen this way, brotherhood is not merely the place where love appears; it is the infrastructure that carries mercy to where it is needed most. Hospitality generates presence; presence makes nasiha (sincere counsel) possible; counsel permits ta’dib (gentle correction) without humiliation; correction restores purpose; restored purpose returns as khidmah (service). The loop closes, and climate forms. In practice, it looks like: a household that adds two plates without drama; a neighborhood trade that becomes dignity instead of debt; a visit that interrupts despair before it hardens. The Quran names the root: “Hold firmly, all together, to the rope of Allah, and do not be divided… He united your hearts, and by His grace you became brothers.”24 The ecosystem is what that grace feels like at street level—mercy traveling on ordinary routes until the whole city is warm.

Companionship as Formation

If mercy moves through a city like blood, this is the heart that pushes it. The Prophet ﷺ did not assemble audiences; he formed companions. He treated proximity as pedagogy and attention as hospitality. “A person is upon the religion of his close companion; so let each of you look carefully to whom he befriends.”25 This is not a slogan; it is an account of how character transfers. We become like what we draw near.

His method was disarmingly ordinary and relentlessly faithful. He turned his whole body to the one speaking, making listening a shelter where shame could not grow. He trained a city to expect barakah by stretching small food—“The food for two is sufficient for three, and the food of three is sufficient for four”—so that generosity became muscle memory rather than mood. He kept the vulnerable within arm’s reach, corrected without spectacle, praised without flattery. In those micro‑practices, souls were apprenticed into a different way of being.

Later sages only named what his suhba (companionship) had already proved. Sit with the people of God and you carry their scent; nearness transfers state.26 This is why niyyah must precede logistics, why nasiha must ride on affection, or it will not be heard, and why taʾdīb must be gentle, or it will not heal. Formation is not an event; it is a climate of nearness where habits of love are rehearsed until they feel native.

This is the first principle I must bring forward into our very different world: treat companionship as formation. Build circles where attention is habitual, meals are elastic, errands are shared, and confession can be safe without becoming spectacle. Without this engine, we will refine programs and remain unchanged; with it, the broader ecosystem of mercy becomes a school of the soul. In that school, sabr is practiced until it becomes reflex, and tawakkul is learned until interruptions feel like invitations from Him.

Where Barakah Begins

We have not been asked to rebuild their streets; we have been invited to relearn their reflexes. In Madinah, love did not depend on abundance. It depended on niyyah, sabr, and tawakkul. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ trained hearts until generosity became muscle, counsel became shelter, and presence became a school.

If we carry only one lesson forward, let it be this: companionship is formation. It is how Allah grows us for one another and toward Him. Treat nearness as a pedagogy, not a convenience. Make attention a home where shame cannot multiply. Expect barakah precisely where your measures predict shortage, and let sabr hold the door open long enough for that increase to arrive.

Three small obediences begin the rebuilding: turn your whole body toward whoever speaks so listening becomes safety; stretch a meal for one more and expect barakah; keep covenant when mood fades, letting sabr and tawakkul hold the door open until the increase arrives.

The rope of Allah is held together by these quiet choices. When they are repeated, they harden into culture. When they are neglected, programs grow while people shrink. Let us therefore attend to the seed, not the scaffolding: sincerity before strategy, presence before performance. The plans and floor‑lines will come. First, we choose to stay, to see, and to move toward one another—believing that what leaves the hand returns to the heart as mercy.

With Allah are the openings, and with Him is the increase.

Watt, W. Montgomery. Muhammad at Medina. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1956. 157. Internet Archive. Accessed October 11, 2025. https://archive.org/details/muhammadatmedina029655mbp.

Anjum, Ovamir. “The ‘Constitution’ of Medina: Translation, Commentary, and Meaning Today.” Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research, February 4, 2021. Updated July 22, 2024. https://yaqeeninstitute.org/read/paper/the-constitution-of-medina-translation-commentary-and-meaning-today.

Kallek, Cengiz. “Socio-Politico-Economic Sovereignty and the Market of Medina.” IIUM Journal of Economics and Management 4, nos. 1–2 (1996): 1–14.

Martin Lings, Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources (Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 1983), 63–64.

Ibid., 88–93.

Quran 16:41.

Quran 8:26.

Quran 59:9.

Ahlus-Suffah (“people of the shaded platform”) were a group of poor Muslims, who were given permission by the Prophet Muḥammad to live in a corner of the Madina mosque. They were “guests of Islam” with no families or means; the Prophet ﷺ routinely directed that they be fed and shared gifts with them. See “Ahl al-Suffa .” The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions. Encyclopedia.com. (October 6, 2025). https://www.encyclopedia.com/religion/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/ahl-al-suffa and Sahih al-Bukhari 6452.

Quran 9:71.

Quran 5:2.

Quran 3:103.

Ibn ʿAṭāʾillāh al-Sakandarī, The Book of Wisdoms (al-Ḥikam), trans. Victor Danner (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), Aphorism 43.

This is soooo beautiful mashallah

Allah bless you sheikh