The Trials of Transition: What We Leave, What We Carry

To leave is to lose, but also to trust that Allah writes more than we can see.

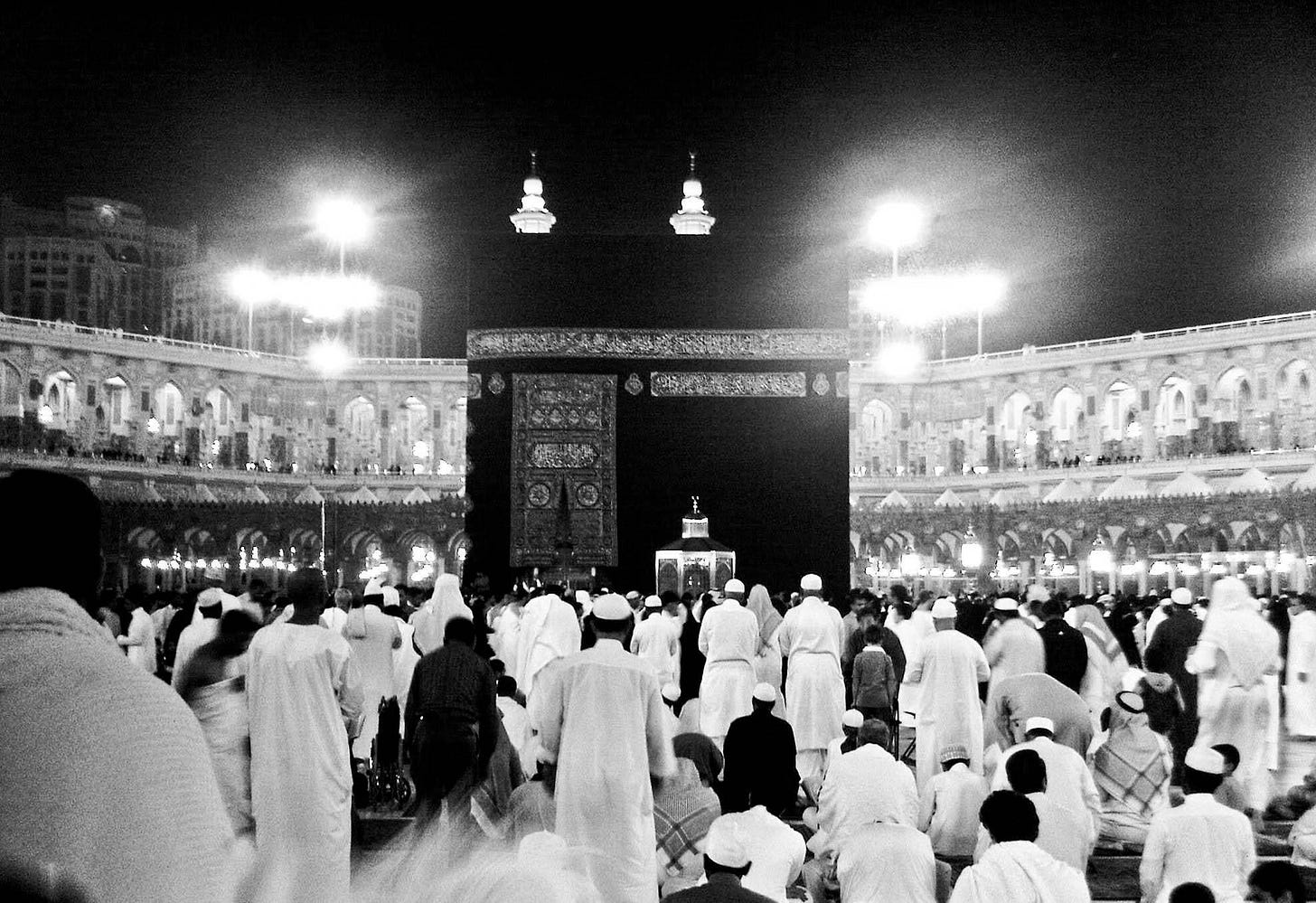

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was born, and spent the first fifty-three years of his life, in Makkah. He belonged to Quraysh, the ruling clan, and to Banu Hashim, a tribe that had lived in the city for generations. He ﷺ was as Makkan as one could be—his childhood, his kinship ties, his earliest friendships and memories were woven into its valleys and markets. He ﷺ loved the city deeply.

At forty years of age, revelation descended upon him, and with it came both embrace and rejection. His beloved wife, Lady Khadijah, accepted his call immediately, followed by Imam Ali, Abu Bakr, and Zayd ibn Haritha—may Allah be pleased with them all. Yet it was also his clansmen who resisted most fiercely: Abu Lahab, Abu Sufyan, and others. For thirteen years he proclaimed the oneness of Allah, enduring mockery, boycott, and persecution.

Finally, when Allah opened the way for migration, the Prophet ﷺ departed his beloved city—not out of desire, but out of necessity. Standing on an eastern hill, he looked back with aching love and apostrophized:

“By Allah! You are the best of Allah’s earth, and the most beloved of Allah’s earth to Allah, and if it were not that I was expelled from you I would not have left”1

That single statement carries the tension of every human transition: the grief of leaving what is beloved, and the courage of stepping into what is unknown. It is here that my own reflections on Makkah, Boston, and Virginia begin.

Makkah: Formation + First Anxiety

By the spring of 2016, I had lived in Makkah for nearly a decade. Despite its reputation for being rough, even abrasive, it was home. It raised me.

It was in Makkah that I felt the sharp sting of grief for the first time—losing loved ones, leaving behind family. It was in Makkah that I felt the sweetness of joy—marrying my wife, visiting Madinah. It was where I signed the lease for my first apartment and bought my first car. It was the soil where formative friendships grew—Imam Farhan Siddiqi, Mustafa Davis, Sh. Yasir Fahmy—and where my passion for Islamic spirituality and mental health was first awakened.

Life there was its own rhythm: traffic laws treated like suggestions (cars commonly drive in between lanes, as if the lines are to mark the center of the car, and overtake you on highway on and off ramps), bureaucracy requiring endless signatures, a degree plan stretched over nearly two hundred credit hours. The tribalistic nature of society often made it lonely for foreigners, but it was a system I understood.

I remember asking fellow students, just two years into my Makkan chapter, “What will you do after graduation?” Some hoped to remain, others had no plan. I did not know why, but even in those early years I could sense that my time there would not be permanent. Perhaps it was simply youth, the restlessness of knowing that after study comes something else. Yet as the years passed, I grew comfortable, and before I knew it, graduation was approaching.

That comfort gave way to anxiety. I was married, with children, and had no job lined up. I remember sitting in class one day, my mind racing. I bolted as soon as it ended, ran to an empty library, and collapsed in an aisle, trembling in what I now recognize was a panic attack. Another time, confiding in a brother during ʿUmrah, he told me, “You’re like the brothers who were in jail and now they’re being released.” His words stung—because they were partly true.

Unlike the Prophet ﷺ, no one was expelling me from Makkah. My time had simply come to its natural close. Yet the grief of leaving what was familiar, and the dread of reentering a world I no longer knew—the United States—felt suffocating.

And then Allah opened a door. Sh. Yasir Fahmy graciously accepted me as his understudy. It was not an answer I had engineered. It was given. And yet, even with that blessing, I carried the Prophet’s words in my heart: “If it were not that I was expelled from you, I would not have left.”

Boston: Scaffolding + Community

If Makkah was the soil of my formation, Boston was the scaffolding that helped me stand. Not because of the city itself, but because of the people—most of all, Sh. Yasir Fahmy and Yusufi Vali.

In “From the Etiquettes of Mentorship” I mentioned,

When I arrived in Boston to serve under Sh. Yasir Fahmy, it was my first time working so closely with a scholar. I was a naive and inexperienced Blackamerican Saudi graduate from Northern Virginia and Sh. Yasir is an Egyptian-American Azhari par excellence from Northern New Jersey. We could not have been from more different worlds; so much was difficult for me to grasp. Initially, I thought the relationship was unhealthy. But, through constant consultation with another mentor, I was shown my naivety to the world of khidma and tarbiya (the process of cultivating adab) and how to understand and eventually serve Sh. Yasir.

Then there was Yusufi, one of the community’s unsung heroes. He was not a scholar but a servant—“the consummate public servant, deeply beloved by the people whose lives he touches.”2 As Executive Director, he carried burdens far beyond his role. He pushed me into interfaith work through the Greater Boston Interfaith Organization, into counseling training at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Refugee Trauma and Resilience Center. After khutbahs (sermons) or halaqas (lectures), he gave critical feedback. And when payroll was uncertain, he reassured staff that he would protect them—and he did. He carried the community with a quiet, relentless compassion.

Still, even after Yusufi resigned and eventually Sh. Yasir left Boston, there was the community itself. Families took my wife and children as their own. Sisters treated my kids like nieces and nephews, whisking them away to the beach, buying them chocolate. Brothers appeared in my office with unexpected gifts. People traveled with us, laughed with us, prayed with us. Bonds were woven in those years that still endure.

Leaving Boston was bittersweet. Bitter, because we had finally begun to feel stable, rooted. Sweet, because the move brought us closer to family—back to the DMV. It felt less like exile, and more like a gentle nudge forward.

Virginia: Return + Responsibility

After fifteen years away, returning to Virginia felt like rediscovering a childhood home—familiar, yet changed.

At the MAS Community Center, I found myself among youth who trusted me with their unfiltered honesty. Gen Z is unencumbered by social expectation once trust is earned and these jokers asked about everything—boys about advances at school, girls about BBLs. Their questions were raw, but they also listened. In those two and a half years, we traveled together, ate together, and sometimes they called me on the brink of despair. To be invited into their lives was a profound honor.

At ADAMS, the scope widened. Six branches, thirty-three Jummah prayers, seven Imams under Imam Magid and Sh. Abd Ar-Rafaa Ouertani. My work shifted to primarily young professionals and pastoral care. Through Qahwa (ADAMS in-house coffee shop and third-space), I explored mental health in an Islamic frame. Through Qurtuba (ADAMS education department), I designed a graduate-level syllabus, teaching both Family Systems in Islam and classical texts like Ibn Qudama’s Mukhtasar Minhaj al-Qasidin.

ADAMS felt like a culmination of my experiences—childhood in diverse mosques, studies in Makkah, counseling training. It also became fertile ground for writing: outlines for books, reflections, essays.

Leaving ADAMS, and MAS before that, was unlike leaving Makkah or Boston. It was not panic, nor bittersweetness, but fear of letting people down. Communities become family, and stepping away always feels like betrayal. My beard's grey hairs continue increasing under the weight of that responsibility.

Processing Transitions: The Wilderness of Waiting

What unsettles me about transitions is not only what they take away, but the space they create. That gap between what was familiar and what has not yet begun. It feels like wilderness—vast, unstructured, and silent.

I think of the Prophet ﷺ standing on that hill outside Makkah. He loved his city, its stones and its air. And yet, he had to leave. In that pause between departure and arrival, he was suspended in the unknown. That space has always felt haunting to me, because I know it too well.

In Makkah, it came as panic. A tightening of the chest, racing thoughts, the sensation of drowning while surrounded by people. I remember hiding in the library aisle, praying that no one would see me, ashamed that faith did not insulate me from fear. That wilderness taught me that anxiety is not solved by ideas alone. Sometimes it simply has to be survived, breath by breath.

In Boston, the wilderness took a different shape. It was not panic but bittersweetness. Packing boxes while neighbors hugged us, my children asking why we had to leave friends who felt like family. There were nights I lay awake asking Allah why stability is allowed to last only long enough for one to taste it. The Qur’an says, “We alternate these days ˹of victory and defeat˺ among people so that Allah may reveal the ˹true˺ believers.”3 At that time, those words did not soothe me; they unsettled me. Why should sweetness have to be taken away just when it begins to feel like home?

In Virginia, the wilderness was quieter but heavier. It was the fear of letting people down. Every goodbye felt like betrayal. Crafting a farewell letter carried the risk of disappointment. I love the people, and I know they love me. Yet love itself made leaving more painful.

Over time, I have learned that these moments demand two things: first, the willingness to pause and reflect; second, the courage to act.

Pause and Reflect.

Transitions are bookmarks in the story of our lives, moments when Allah allows us to stop and remember. To look back at how He carried us before, and to trust He will carry us again. Each move—Makkah, Boston, Virginia—left behind a marker in my history, a reminder that anxiety may blur the present but never erases His past generosity. Reflection also opens space for growth. Each figurative hijra (migration) reveals something new I must learn—sometimes resilience, sometimes gratitude, sometimes the humility of letting others carry me when I cannot carry myself.

Sphere of Influence.

Reflection also forces me to measure what lies within my control and what lies beyond it. Anxiety thrives on pretending I can master the future. But the Prophet ﷺ taught us to act while knowing the outcome rests with Allah. Abdullah ibn Amr ibn al-ʿAs said, “Work for your life in this world as though you will live forever, and work for your Hereafter as though you will die tomorrow.”4 My responsibility is only to tend to the sphere Allah has given me—the conversations I can have, the preparations I can make, the prayers I can lift. Beyond that, the future belongs to Him.

Act.

After pausing, and after trying to discern what lies within my sphere of influence, I’ve learned that I cannot remain still forever. The Qur’an says, ‘Work, for Allah will see your work, and His Messenger, and the believers…”5 Acting does not mean I control the future; it only means I try to honor the present. In Makkah, that looked like finishing my studies even as uncertainty pressed in. In Boston, it meant attempting to embrace mentorship, even when I did not always understand it. In Virginia, it was simply showing up for people, even as my own heart wavered. My steps have been small, often faltering, but they have kept me moving. Sometimes the only way anxiety loosens its grip is when we take even the smallest step forward, trusting that Allah will meet us there.

Transitions are not tidy arcs of growth. They are jagged. They are humiliating. They are often more wilderness than clarity. But if I pause and reflect, remember my personal history, discern my sphere of influence, and then act within it, I find that Allah meets me there—not always with the answers I crave, but with the strength to take the next step. And sometimes, that is enough.

Conclusion: Moving When Allah Calls Us

The Prophet ﷺ did not leave Makkah by choice. He exhausted every possibility there, bore years of rejection and persecution, and only when he was forced did he look north to a new beginning. His love for the city never wavered, but when Allah called him forward, he obeyed.

We too move when Allah sends us signs. Sometimes those signs are gentle—a graduation on the horizon, the quiet close of a chapter. Other times they are more direct—a phone call from a mentor, the unmistakable weight of responsibility.

For me, it was all three. The pressure of graduation in Makkah forced me to reckon with a future I had deferred. The call from Sh. Yasir Fahmy opened a door into mentorship and service. And most recently, after resigning from ADAMS, Allah blessed me with another door opening: I stepped into a new role at a startup philanthropic foundation as Program Director and Imam in Residence, tasked with creating a nationwide fellowship for Imams.

Each of these was a figurative hijra. Each demanded that I leave behind what I loved, embrace what I did not yet know, and trust that Allah’s plan was greater than my own. We do not choose the timing. We do not always choose the place. But when Allah calls us to move—by force of circumstance, by the closing of a door, or by the gentle opening of a new one—the task is not to resist. It is to walk forward. Carrying love for what we leave. Carrying trust in the One who guides us to what comes next.

As we face the trials of life’s transitions, may Allah help us pause and remember His care, discern our steps, grow through what He sends, and steady our hearts to walk with trust as He carries us closer to Him. Ameen!

Ultimately, with Him is all success.

The Prophet ﷺ went on to be warmly embraced by the people of Madinah (singing songs of joy as he entered), established it as Islam’s religio-political capital (and it remained so until the year 36/657), and never returned to live in Makkah again.

Griswold, Niki. “Yusufi Vali, Wu’s outgoing deputy chief of staff, bids bittersweet farewell to Boston City Hall.” Boston Globe. August 13, 2024. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2024/08/13/metro/yusufi-vali-boston-mayor-outgoing-deputy-chief-of-staff/

Quran 3:140.

Ibn AbiUsama, Al-Harith (d. 282/895). Baghiya Al-Baaith ‘an Zawaid Musnad Al-Harith. Compiled by Nuridin b. Ali Al-Haitimi. Madinah, KSA: Khidmah Al-Sunnah wa Al-Sirah Al-Nabawiya, 1992. Vol. 2, 983. Accessed via https://shamela.ws/book/13160/1739.

Quran 9:105.