The Chatbox Can Listen, But It Can’t Care

Why AI Can’t Replace the Sacred Bonds of Human Companionship

One of my youngins—let’s call him Fulan—met a sister on one of the apps, and things were really looking promising. He passionately seeks companionship, and after a series of long, vulnerable phone conversations, he felt like they genuinely clicked. They checked off each other’s boxes, shared values, and had strong compatibility. He was excited—hopeful even—when sharing the news with me.

Despite his age, Fulan is a serious and grounded young man. MashaAllah, professionally, he has landed a solid job right out of college and has been excelling ever since, thanks to his technical skill, ambition, and social intelligence. Personally, he is deeply self-aware and very intentionally seeks mentorship. Also, emotionally, because of his past trauma, he’s an open book—unafraid of vulnerability or difficult conversations.

But as the relationship progressed, that very openness began to overwhelm the sister. Though she was well-accomplished and emotionally intelligent in her own right, she began to feel uneasy. And rather than process those emotions with a trusted friend, mentor, or even him—she turned to ChatGPT.

Unbeknownst to Fulan, she had been using the chatbot regularly as her therapist. When she asked for guidance, the AI interpreted the intensity of her feelings as a red flag—labeling it “moving too fast” and recommending she end the relationship to protect her emotional well-being. She took the advice immediately and relayed the decision to Fulan, word for word. No conversation. No discernment. Just a prompt and a parting message.

Fulan was completely blindsided.

The advice may have been logical, but it lacked the emotional, spiritual, and relational nuance she might have received had she spoken to a human being—someone who could weigh not just patterns and probabilities, but care, context, and consequence.

Months have passed since Fulan shared how the relationship ended. But as OpenAI (ChatGPT’s parent company) now moves to add new mental health guardrails to its chatbots, I keep coming back to this question: Why are so many people turning to AI to mediate their hearts? What happens when algorithms mediate our trust, intuition, and attachment?

This is not a critique of individuals—especially not of the sister in the story. Rather, it’s an attempt to interrogate a deeper crisis: a crisis of connection. Machines can reflect feelings, but not mercy. They can simulate presence, but not offer companionship.

As AI becomes a surrogate therapist and emotional compass for so many, this paper explores the ethical, psychological, and spiritual dangers of outsourcing our inner lives to machines. The crisis we face is not rooted in technology itself, but about what we’ve lost: real presence, meaningful bonds, and trust in God and one another. What we need is not smarter algorithms, but suhba (sacred companionship) and community are the healing response.

Sociological Roots

Due to a myriad of factors, since the 1980s America has gradually shifted away from collectivistic values to hyper-individualism. We shifted from “we” to “me.” So, while emotional self-sufficiency is now idealized, it comes at a high cost: isolation, shallow connections, and loneliness. It wasn’t by surprise either. French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville (d. 1859) said in his seminal work, Democracy in America, almost a century before shift, “Individualism is a calm considered feeling which disposes each citizen to isolate himself … and withdraw from the mass of his fellows.”1 Or, as sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (d. 2017) said, “What used to be mutually binding togetherness is now more like a succession of loosely tied episodes. Easy to enter, easy to abandon.”2

Fulan didn’t rely on traditional methods (i.e., family connections or “rishta“ aunties) to find a spouse, he turned to matrimonial apps. It wasn’t due to a lack of trying either. Our communal structures—extended family, neighborhood bonds, and spiritual communities—have collapsed and left us untethered. Even our traditional third spaces—like houses of worship, local parks, etc.—no longer function as default gathering places. We engage with them on a personal-need basis, not casually or looking for socialization, and consequently emotional and spiritual mentorship has waned, particularly across generations.

In the void of enduring relationships and genuine community, many turn to social media, therapy memes, parasocial “friendships,” and AI chatbots. These sources give the illusion of connection, but lack risk, sacrifice, and commitment. The algorithms provide a tailored response—offering predictable and nonjudgmental replies, safety from rejection, and 24/7 availability—but with no real presence. As soon as Fulan found out that the sister was consulting ChatGPT for advice he was worried about the potential outcomes. The emotional engagement feels less risky, but also less real (to those who know it). It’s a simulation; AI emotional intelligence is only ever one-sided. They cannot sit with pain, hold silence, or offer mercy. ChatGPT cannot differentiate between the proverbial butterflies associated with a burgeoning relationship and someone using intense language prompts from legitimate safety threats.

The rise of AI therapy is not just about innovation, it’s about insulation. We are not merely seeking answers; we are avoiding the vulnerability of being known. What we need is not more personalized data, more personalized presence. Not smarter machines, but committed hearts.

“Secular modernity has accustomed us to the therapeutic values, not salvific ones.”3

–Sh. Abdal Hakim Murad

Why AI Fails

Machines can mirror, but not mediate

AI excels at recognizing language patterns and mirroring back emotional content, but it lacks awareness of the embodied self. Chatbots, like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, is a large language model (LLM) that cannot read posture, tone, or spiritual states—or recognize when someone needs silence instead of speech. Sociologist Sherry Turkle has an entire book—Alone Together— dedicated to “we expect more from technology and less from each other.”4

Hierarchies of Values

AI operates on probabilistic logic and secular ethics: minimize discomfort and maximize perceived well-being. Even if programmed with ethical reasoning and given guardrails specifically for mental health intervention, it still has ethical risks.

“They may inadvertently reinforce negative thought patterns or fail to recognize severe symptoms that require immediate professional intervention. Relying on these chatbots could discourage individuals from seeking help from human professionals, leading to delayed treatment of serious conditions. In addition, both types of chatbots raise privacy concerns, as sensitive personal data could be mishandled or exploited, further compromising users’ well-being. For chatbots that are not specifically designed for depression intervention, this risk might be even higher.”5

Contrarily, Islamic ethics is guided by maqasid al-shari’ah (the higher objectives of the Sacred Law— safeguarding faith, intellect, life, lineage, and property), not utilitarian ethics. The ends do not justify the means, and the maqasid is an entire philosophical framework that cannot be determined absolutely by machines. Only a human, specifically with extensive personal and technical training, can properly assess what will help someone determine spiritually transformative or morally redemptive.

Psychological Flattening

Determining emotional well-being is a dynamic and nuanced process shaped by a person’s unique social, spiritual, and cultural history. Psychology, unlike the natural sciences, is interpretive and relational by nature. Therapeutic success often depends on personal trust, patience, and embodied rapport. All of the seminal figures of psychology—Freud, Jung, Rodgers, and others—-engaged with meaning, trauma, and identity (not universal constants), making it fundamentally incompatible with algorithmic certainty. AI can recognize patterns, but cannot access the lived meaning or sacred aspirations behind them. Additionally, “AI chatbots may oversimplify complex mental health issues and risk normalizing emotionally passive responses.”6 For Muslims, emotional healing is not just about functioning but about walking towards Allah, a far more comprehensive process.

Empathy Without Presence

Compassion without shared suffering becomes either clever mimicry—or worse, pity. Pity sees pain and is apathetic, if not recoil, whereas compassion sees pain and draws near; pity reinforces hierarchy, whereas compassion fosters solidarity. In Islam, rahma (mercy) is not a passive state, it is a divine embodied action. Real empathy requires presence, witnessing, and a willingness to carry part of the emotional or spiritual load. The Prophet ﷺ wept with the grieving,7 walked with the wounded,8 and uplifted the fallen.9 AI lacks soul and suffering—can simulate concern, but they do not feel with the us.

Misguided Trust + Hallucinations

In addition to emotional flattening, there are also cognitive risks: LLMs inspire trust due to their eloquence, not wisdom. Their confidence masks shallowness and their errors cannot be held accountable because they actually don’t know what they’re talking about.10 Furthermore, they hallucinate—confident about false outputs. That’s especially dangerous when used for emotional discernment. As we saw with Fulan’s situation, misguidance from AI can rupture relationships, but also delusion and “AI psychosis.”11

AI can respond, but it cannot relate. It does not witness, it does not remember, and it does not love. When life becomes heavy, we do not need outputs—we need people. People who show up, who carry burdens with us, who remind us of God when we forget ourselves. This is the work of suhba—not a feature or tool, but a sacred bond that grounds us in mercy, mutual accountability, and shared striving.

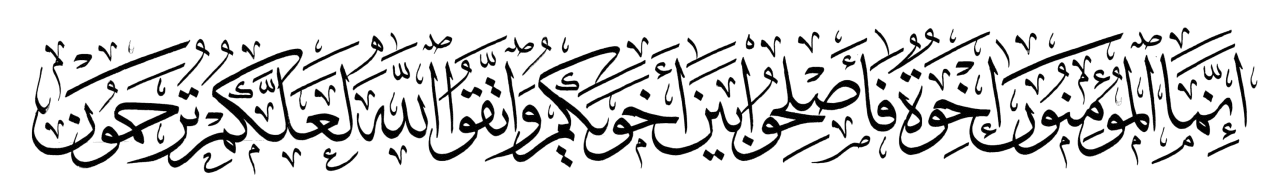

"You see the believers as regards their being merciful among themselves and showing love among themselves and being kind, resembling one body, so that, if any part of the body is not well then the whole body shares the sleeplessness (insomnia) and fever with it."12

–Prophet Muhammad ﷺ

The Deeper Spiritual Struggle

If AI’s rise in emotional and spiritual life exposes a technological turn, beneath it lies something deeper—a spiritual crisis that runs quietly beneath our modern habits. This is not just about digital tools or psychological shortcuts. It is about the state of our hearts, our fears, and the deeper conditions that make us reach for simulations instead of souls.

Many people are not drawn to AI because it offers better answers, but because it demands nothing in return. Real relationships come with risk. To open one’s heart to another person is to risk being misunderstood, rejected, or even judged. AI, in contrast, feels safe. It does not ask for vulnerability—it receives it without flinching. But perhaps that’s precisely the problem. The Prophet ﷺ said, “The believer is the mirror of the believer.”13 Mirrors reflect not just the polished exterior, but the blemishes, too. Suhba offers truth with tenderness. But that truth, even when loving, is still uncomfortable. Machines, on the other hand, offer relief without reflection.

For many, the appeal of AI lies in the illusion of control. You can revise your prompt, erase what you shared, ask the same question a hundred different ways until it sounds “right.” You control the speed, the topic, and the depth. You are never asked to pause, to sit in silence, to carry the weight of another. This control is comforting—but spiritually, it is stunting. Growth does not happen on your own terms. It comes when you surrender, when you trust in Allah and allow the unpredictability of real relationships to shape you. Tawakkul (trust in Allah) is not about having power over outcomes—it is about relinquishing control to the One who knows what you need better than you do. As Allah says in the Quran, “And whoever puts their trust in Allah, then He ˹alone˺ is sufficient for them.”14

And for many, there is a simpler reason: We have been hurt. People—teachers, parents, religious leaders, even friends—have failed us. We’ve felt unheard, unprotected, or unloved. So we turn to something we believe cannot hurt us. This is not a sign of weakness, but of wounding. Yet spiritual healing cannot happen in isolation. Rahma cannot be simulated. It must be witnessed. And while AI can mimic language, it cannot carry your story. It cannot remember your pain from last week or recognize the growth in your voice today.

There is also a subtle avoidance at play—not just of people, but of the self. AI allows us to vent, to strategize, to seek comfort—but rarely to confront. It provides clarity without repentance, validation without introspection. But Islamic healing is never about bypassing pain. It is about meeting it, naming it, and asking Allah for meaning within it. Mujahada (spiritual struggle) is not avoided; it is embraced. The soul does not transform through ease—it is polished by striving.

At the core of this turn to simulation is a loneliness that is not just emotional—it is spiritual. It is the ache of the soul to be seen. Not just by people, but by God. And in our avoidance of people, we sometimes also distance ourselves from the places and relationships where we might feel Him most—among the truthful, the striving, the sincere. “O you who believe,” says Allah in the Quran, “be mindful of Allah and be with the truthful.”15 The antidote to spiritual loneliness is not more answers. It is more presence. More witnessing. More hearts that fear Allah and love you for His sake.

This section is not meant to judge. Rather, it is an invitation to look inward. Before we turn to another app, another chatbot, another output, we must ask: What am I really seeking? And what am I afraid of receiving?

Because only when we name the struggle, can we prepare ourselves to receive the gift of suhba—not as a product of ease, but as a fruit of courage. And yet, even in our hesitations and hurts, Allah does not leave us without a way forward. He sends us people—those who remind us of Him, hold space for our growth, and walk with us through the messiness of becoming. This is the mercy and gift of suhba.

The Antidote: Suhba

When the Prophet ﷺ passed his legacy was not preserved because of physical buildings or formal organization; rather he ﷺ left behind him a religion preserved in the hearts of the Sahaba (his companions), Allah be pleased with them. His companions became the Sahaba through being in his presence—they traveled, grieved, and rejoiced with him ﷺ. Real transformation comes through proximity and presence, through suhba. While curricula and programs impart knowledge, the development of khuluq (character) and adab (manners) happens in person.

Suhba ≠ Friendship

Suhba goes beyond friendship: friendship is rooted in affinity and suhba is rooted in intention; friendship is often comfort-based and suhba is growth-based; and friendship prioritizes harmony while suhba prioritizes truth with mercy. The intention is that, through this connection, we have come together for the sake of Allah, hoping to earn His pleasure and shade on the Day of Judgement.16 Through that expansive intention (i.e., seeking the pleasure of Allah), Suhba becomes a covenant, not a convenience; a mirror, not a mask.

Suhba is not a role we perform, it’s a disposition we carry. We don’t find the right person, we become one. It doesn’t appear or disappear based on context (e.g., in the boardroom versus the group chat). Being a colleague or supervisor does not exempt us from our spiritual responsibility of adab. Furthermore, the temptation to compartmentalize—warm and gentle at the masjid, cold and harsh in professional ones—is a modern dysfunction and contradictory to the prophetic model. The Prophet ﷺ displayed consistency and integrity across all settings.

The Prophet ﷺ said, “Kindness is not to be found in anything but that it adds to its beauty and it is not withdrawn from anything but it makes it defective.”17 We mustn’t use professionalism as a license for coldness. Boundaries are necessary, but never at the expense of compassion. It’s because of the richness of suhba that we have higher expectations or kindness, protection,18 and love.19

Sacrifice

Arabs have a saying, “Yad wahid la yusafaq—You cannot clap with only one hand” and suhba is no different. One person cannot carry the weight of the relationship. It doesn’t mean that both people will be the best of friends, but because of their shared intention to earn Allah’s pleasure, both parties have to be willing to contribute. If not, it’s merely a transaction. But, unlike transactional relationships, it isn’t scorekeeping. It’s genuinely striving to care for another and cultivating a relationship where affection turns into trust.

Suhba, like all deep relationships, requires work. But unlike ordinary friendships, it’s spiritual nature calls for a higher level of sacrifice. We must have theocentric altruism, as the Prophet ﷺ said, “None of you truly believes until you love for your brother what you love for yourself.”20 The cost of this sacrifice is ego, time, and emotional energy, but the return is baraka (blessings). Additionally, through sacrifice and service is how we make others feel safe. Suhba dies where entitlement grows and thrives where humility reigns.

Community

If suhba is the seed, community is the orchard. They aren’t defined by the places where people convene— e.g., Masjids and third spaces. Community is the manifestation of suhba en masse, when sacred companionships extend beyond two people and relationship nodes intermesh to a dyadic web of rooted connections. As I mentioned in Cultivating Community: Why the Juice is Worth the Squeeze, “A healthy community is an altruistic and sustainable ecosystem that cultivates a sense of belonging among its members and generates a cohesive confidence rooted in the shared desire to engage, contribute, and serve.”

For more on this topic, please see the paper below.

Conclusion: From Simulation to Suhba

Fulan did not need perfect advice. He needed presence. He needed someone who could sit with him in his confusion, hold space for his hopes, and gently help him discern between emotional turbulence and spiritual clarity. But instead of a person, the sister turned to a prompt. And while the machine may have generated a well-structured reply, it failed to offer what only human beings can give: care, context, and commitment.

His story is not just about a relationship that ended too soon. It is a parable of our time—a cautionary tale about what happens when we allow simulations to mediate the most sacred parts of our inner lives. Chatbots may be available at all hours, but they cannot hold us in silence. They may be trained on trillions of words, but they cannot speak from love. They may reflect back our feelings, but they cannot witness our souls.

What happened with Fulan reveals a deeper trend we now face—it’s not technological, it’s spiritual. It is the loss of a way of being with one another that is rooted in mercy, mutual striving, and remembrance of Allah. We are suffering not because machines are too intelligent, but because our relationships have become too thin, too transactional, too disembodied. We are longing for guidance, but avoiding the vulnerability that real guidance requires. We want to feel known, but resist the patience, humility, and sacrifice that knowing demands.

This is why we must return to suhba—not as a nostalgic ideal, but as a living, breathing necessity. Suhba grounds us. It slows us down. It teaches us how to listen, how to carry, how to be carried. It reminds us that mercy is not optional, that truth must be spoken with tenderness, and that healing begins not in clever advice, but in the shelter of another heart that fears Allah and loves you for His sake.

Fulan may have lost a relationship, but he did not lose hope. That experience became a turning point—not just in how he seeks companionship, but in how he understands what it means to be seen. He learned that discernment does not come from code, but from connection. That healing requires more than output—it requires witnessing. And most of all, he learned that the kind of companionship worth seeking is not fast, frictionless, or filtered through a screen. It is earned. It is built. And it is sacred.

What we need now is not smarter algorithms, but softer hearts. Not better simulations, but deeper relationships. Not convenience, but conviction—that companionship rooted in Allah is still the truest technology of the soul.

And, ultimately, Allah knows best.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. Democracy in America. Translated by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. 482.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000. 14.

Murad, Abdal Hakim. Understanding the Four Temperaments and the Prophetic Way. Cambridge: Quilliam Press, 2014. 22.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books, 2011.

Denecke, Kerstin, and Eva Gabarron. “The Ethical Aspects of Integrating Sentiment and Emotion Analysis in Chatbots for Depression Intervention.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 15 (2024): 1462083. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1462083.

Luxton, David D., et al. “Ethical Challenges and Risks of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health Care.” JMIR Mental Health 10, no. 5 (2023): e38245. https://mental.jmir.org/2023/5/e38245.

Marcus, Gary, and Ernest Davis. Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust. New York: Pantheon Books, 2019. 109.

Hart, Robert. 2025. “Chatbots Can Trigger a Mental Health Crisis. What to Know About ‘AI Psychosis.’” Time, August 6, 2025. Accessed August 18, 2025. https://time.com/7307589/ai-psychosis-chatgpt-mental-health/.

Quran 65:3.

Quran 9:119.

ibid.