Ruminations: 2024

The patterns of this year felt divinely woven—constriction, brokenness, suhba, and hope—each trial and blessing a thread in Allah’s perfect plan.

This post deviates from my usual narrative and pastoral style. Inspired by my friend’s (M. Saad Yacoob) recent posts, this is a collection of loosely connected reflections without providing any specific guidance.

Starting the new year doesn’t usually mark any special significance for me. Perhaps it’s my rebellious streak, wanting to be different than everyone’s New Year’s resolutions. But, for some reason, the last few days I found myself reflecting over last year.

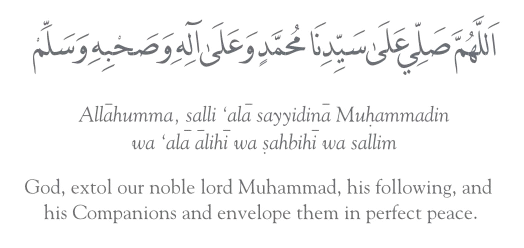

I naturally seek patterns, so I checked my calendar and noticed a few emerging—constriction from blessings, brokenness, suhba, and hope. I noted these themes before going to sleep. The next morning, as I read my daily wird (litany), Wird Al-Asas, a connecting metanarrative caught my attention—the themes matched seamlessly with the four staple adhkar (remembrances) of the wird.

Al-Humdulillah, I am incredibly blessed, and this paper is not intended to be a pity party. Even what might have been a bitter experience is nothing compared to so many nationally and internationally. Instead, this is a chronological and thematic reflection on my 2024 in effort to show gratitude and provide a counter-perspective to the self-flagellation commonly found in religious discourse.

Constriction

Sometimes, blessings come with their own challenges. Imagine starting to exercise after a long hiatus. We must increase our caloric intake (ideally good calories), change our sleep patterns, and adjust to fatigue’s effect on our disposition. It is objectively a good thing for us, but it is still an incredibly taxing process, especially in the beginning, physically and mentally.

As we lift weights, we constrict our muscles, seeking muscular hypertrophy (to build our muscles stronger). The process cannot happen without constriction. This growth cycle—breaking down what exists to rebuild anew—is often uncomfortable and inconvenient.

With time, our bodies change; they become slimmer and more defined, and so does our relationship with clothes. They begin to sag and no longer fit. It can create an array of feelings: Are we frustrated because we now need a new wardrobe? Are we proud of all the hard work we put in and the newfound confidence that accompanies it? Or do people’s unfamiliar compliments make us feel insecure and anxious, worried about what they previously thought of us?

As we welcome the new, with all its complexity, sometimes we can forget about the Old. Allah is Ever-existing, always was, and always will be God Almighty. This is why “HasbnAllah wa ni’mal-wakil” is a powerful statement. In its brevity, it sums up and reminds us of a profoundly theological Truth. Whether our new circumstances are an increase or a deficit, Allah is all we need; everything else reminds us who we (weaknesses and strengths) are and who He is (absolutely perfect and majestic).

Once something new loses its luster, it becomes mundane, and we can grow accustomed to constriction. Just because the lactic acid build-up of constriction no longer burns, it shouldn’t be permission for neglect (e.g., our form) or abuse (e.g., overworking ourselves). While we focus on achieving our goals, we mustn’t overlook the role of intentionality in our consistency. We must remember (and know) that Allah is all we need.

In our headlessness is where Shaytan Al-Rajeem (Satan the Accursed) lurks and waits. As Bane famously told Batman in The Dark Knight Rises, “Oh, you think darkness is your ally. But you merely adopted the dark; I was born in it, molded by it. I didn't see the light until I was already a man. By then, it was nothing to me but BLINDING!” We mustn’t forget, “What an excellent Guardian is God.” Everything is by His permission—the bitter and the sweet, times of expansiveness and constriction.

Brokenness

For whatever reason, I have always had a deep relationship with music. Due to my life’s experience—let’s just chalk it up to being Black in America (or a predominantly immigrant Muslim community) and ignore everything else—my go-to response to challenging emotions is disassociation and repression. Music is often a tool; it not only provides words I don’t always have for my feelings, but it is sometimes an entryway for me to feel what is numb. On many occasions, I found Linkin Park’s “In the End” the tool of choice.

Trauma can cause a sense of brokenness, shattering our lives into countless pieces. As victims collect the shards to piece together what was, depending on the age and severity of the trauma, their self-image kintsugi gets tainted.1 What remains is entirely different, changed but integral nevertheless.

“I kept everything inside

And even though I tried, it all fell apart

What it meant to me will eventually be

A memory of a time when I tried so hard”

Sometimes, feelings of brokenness are triggered by new experiences. Despite being years (decades!) after the initial traumatic experience, this latest event is painful. It completely alters time, violently bringing our past emotions to the fore. We go into self-preservation mode, resorting to whatever coping mechanisms we learned (e.g., dissociation or repression) to manage the pain.

“I tried so hard and got so far

But in the end, it doesn't even matter

I had to fall to lose it all

But in the end, it doesn't even matter”

When I reflect on when the “In the End’s” chorus resonates with me, it is always during strife. If I’m honest with myself, it’s probably when I’m triggered. But, if I’m also honest, my trauma, my emotions, my nafs (inner reality)—call it what you want, because names defining the specific thing is less important at this juncture—lead me to turn inwards and forget about God. Astaghfir Allah Al-Azim! Trauma causes the shards of my past to cut through the nicely curated veneer of now despite my efforts. It exposes everything beneath all the theoretical knowledge and intellectual reasoning, leaving the reality of my heart bare.

I say “Astaghfir Allah Al-Azim” not in a judgemental way but because our hearts and minds are delicate, and what we expose them to is really important. If broken glass is in the open, we must handle it with care. Care for the feelings, not making the wound worse, but also care that we don’t create another injury in the process.

Perhaps I’m overthinking it, but LP’s frontmen, Mike Shinoda and Chester Bennington, are singing passionately about heartbreak, but their lyrics are incredibly nihilistic. Although we were injured and retreat was necessary, we lost the battle, not the war. For believers, everything matters. And, because of our vulnerability, this is when we need to be even more mindful of Allah. How we rebuild ourselves is dependent on it. Do we pour emotional salt on our wounds with unhealthy thought processes (i.e., ideas and beliefs about ourselves and/or the world), or do we do the difficult work of kintsugi (i.e., healthily processing our emotions and turning to Allah)?

Ibn Ataillah al-Iskandari (d. 709/1310) said, “Nothing pleads on your behalf like extreme need, nor does anything speed gifts to you quicker than lowliness and want.”2

Suhba

Allah says in the Quran,

“And patiently stick with those who call upon their Lord morning and evening, seeking His pleasure. Do not let your eyes look beyond them, desiring the luxuries of this worldly life. And do not obey those whose hearts We have made heedless of Our remembrance, who follow ˹only˺ their desires and whose state is ˹total˺ loss.”3

For years, I’ve been insecure about my role in the community. I’ve always known I’m a “people person,” but what does that mean in the context of Imamate? I am not a hafidh (memorizer) of the Quran, can’t quote off a bunch of Hadith, haven’t memorized a bunch of books, and don’t have many ijazas (certificates). Since I graduated, I felt a profound sense of imposture syndrome. There have been so many occasions when I was with Sh. Yasir Fahmy and thought, “Oh boy, they’re going to realize I’m just the cheap knock-off version of him!”

Sometimes, we only recognize things by their opposites. It hit me when I returned from a week-long trip with teachers and peers in August. When I’m in suhba (companionship), I’m with kin. Regardless of my hierarchical position—I was the youngest, made coffee, and put out the prayer rugs for others on this trip—I feel respected, valued, and empowered. I feel loved.

I have come to accept that suhba is what I am about. It‘s what I was trained to do, and is all I want to do on every level—on an individual level (e.g., pastoral care and mentorship) and a communal level (e.g., service and education). Everything I think about revolves around it, and that is not random. I want others to feel loved.

Allah is the King, and I am his servant. I am only responsible for myself and what’s within the extent of my control and capacity. Who cares what others think when Allah is the Real? We “stand in need of Allah, but Allah ˹alone˺ is the Self-Sufficient, Praiseworthy.”4 So, no more running from the gifts he’s placed in me. I’m embracing it and leaning in, InshaAllah.

La Ilaha illa Allah!

Hope

This year was crazy for me, Al-Humdulillah. On top of what was (and still is) transpiring around the world—the genocide in Gaza, famine in Sudan, and the list goes on—I had a barrage of personal challenges. But, one thing that I found a source of solace is the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

He experienced it all—physical injury, betrayal, loss of children and loved ones, character assassinations, etc.—while having spiritual and social responsibilities as prophet and governor. As I mentioned in Perspective: A Quranic Hermeneutic of the Isra Wal-Mi'raj, despite all his challenges, “… we never see any effect of that in how he lived with and treated others.” So, not to spiritually bypass my own challenges, Al-Humdulillah, I have been doing a lot of work to remedy my own, I realized somewhere towards the end of the year that this is like a badge of honor. If He ﷺ had challenges, perhaps I need to go through mine to become more like him ﷺ.

I ended the year emotionally drained. All the aspirations and dreams I had were thwarted, and there’s no sign of change to come anytime soon. Yet, I’m hopeful. Allah tells us, “Perhaps you dislike something good for you and like something bad for you. Allah knows, and you do not know.”5 I have already seen how last year, let alone my entire life, my challenges become growth opportunities, how constriction protected me from worse harm, and how brokenness became the foundation for building.

Reflecting on my emotional challenges, I try to imagine the Prophet’s ﷺ. How did he ﷺ feel after his community testified to his trustworthiness, and then his uncle turned around and belittled and cursed him? How did it feel during the Battle of Uhud when his companions didn’t heed his warning and abandoned their posts? How did it feel for him after reaching a more senior age, when his firstborn son passed away at the age of two?

The Prophet ﷺ is my source of warmth amid challenges. I am responsible for being ethical, seeking good consultation, and trying my best. The rest I leave up to Allah.

May He bless this new year with openings, healing, and growth. May He draw us closer to His beloved ﷺ, hoping we, too, become beloved (with goodness, ease, and well-being). Ameen!

Ultimately, with Allah is success.

“Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with urushi lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum.” See Kintsugi on Wikipedia.

Ibn ʿAṭāʾ Allāh. The Book of Wisdoms: Kitāb al-Ḥikam. Translated by Victor Danner. New York: Paulist Press, 1978. 78.

Quran 18:28.

Quran 35:15.

Quran 2:216.