Humility: A Non-Hajj Story

The disappointment of being rejected from performing Hajj with a beloved teacher forced me to explore humility in the company of another.

At the beginning of this year, Sh. Yasir Fahmy’s team shared that this year he would be leading a group on Hajj, and I immediately messaged him, “I’m coming! You need me there. Let’s make it happen!” Al-Humdulillah, I am blessed to have lived in Makkah. I had performed Hajj many times before, so what concerned me wasn’t making Hajj; I wanted to make it with Sh. Yasir and, more importantly, I saw this as an opportunity to serve him. I didn’t mince my words either, “Hajj [is difficult]. I hate it, and love it too. [But], I just know you will need a Khadim (servant) and I’m the #1 draft pick.”

“I don’t need a tour guide, I need a grunt,” Sh. Yasir told me. I responded, “Shaykh, I have done the job before, Al-Humdulillah. I speak Arabic [fluently] and I know Makkah very well. I’m your man!” After the short conversation, I was honored he accepted, and we spent the next five months planning. There were countless meetings—some with Shaykh alone, the travel agency, the Prophetic Living team, and then the hujjaaj (pilgrims) that were coming with us—and things were starting to get serious.

In 2022, I led a group from my Masjid on a trip to Umrah. It was the first time I had returned to Saudi Arabia since graduating six years prior. Also, I was blessed to have my wife with us. After a long journey, with a layover in Istanbul, we arrived in Jeddah wearing Ihram. After my wife went through immigration, I handed over my passport to the officer. He checked my visa and asked me to scan my fingerprints, but then he paused. He asked me if I had ever been deported from Saudi before. I told him, “No, I lived here for ten years and graduated from Umm al-Qura University." Despite his confusion, after six hours of waiting without an answer, I was sent back home.

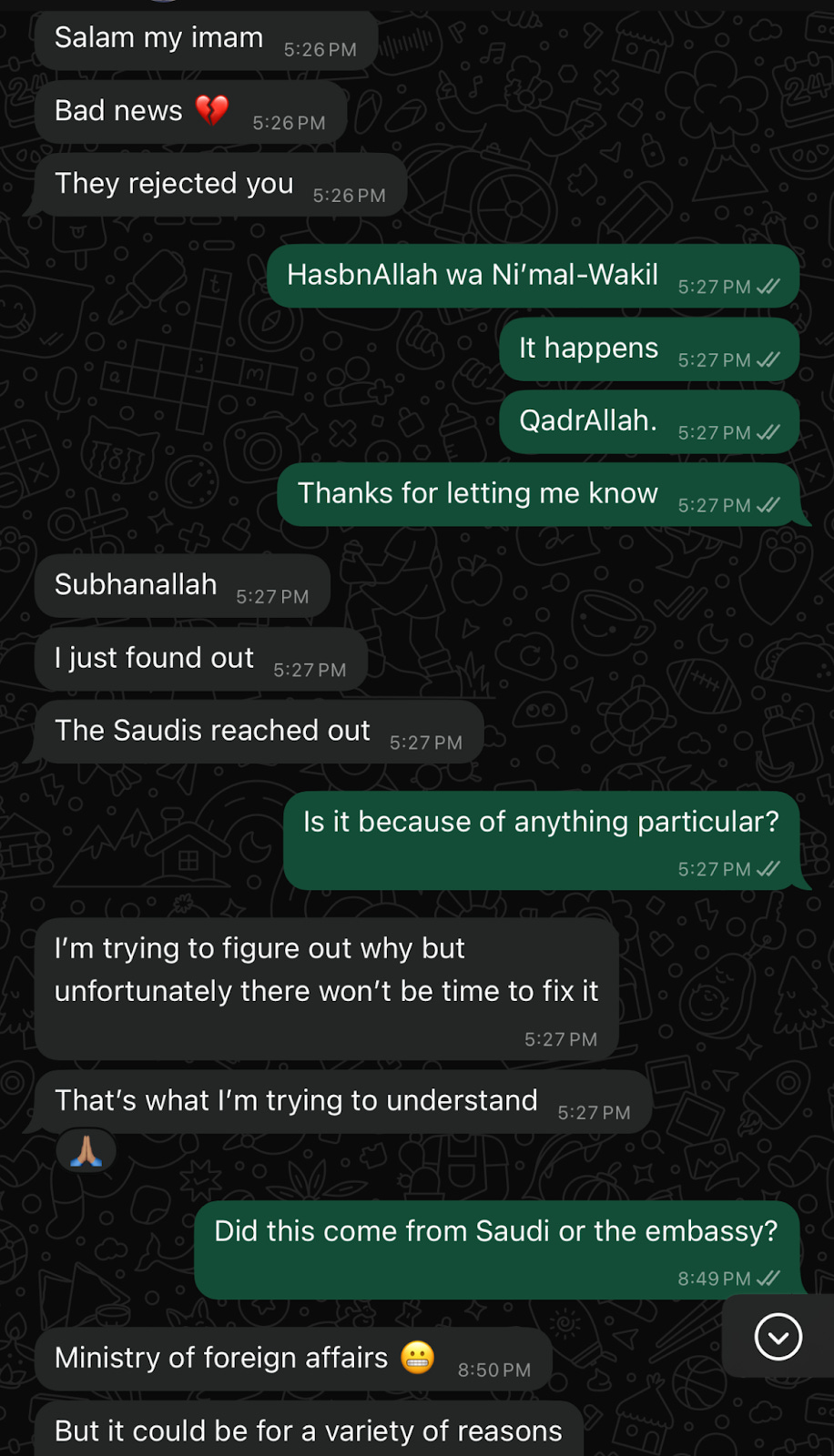

Until today, I don’t know why this happened, but other graduates of Saudi universities who were in the same situation had their problems resolved, and because my name was submitted with theirs, I thought I was good to go. Now, three years later, with the opportunity to make Hajj, I was relieved to have my passport cleared to be a Hajj tour guide. However, just two weeks before my departure, the owner of the travel agency sent me a message, informing me that my Hajj visa had been rejected.

A Lesson in Faqr

Disappointment

I try to keep my expectations as low as possible, especially when things are outside of my control. The higher the anticipation level of things is, the less excited I get. I received the visa update while sitting at my brother-in-law's college graduation party at the table with my family; I closed my phone, went back to the festivities, and didn’t mention it until we got home.

I hoped miraculously something might change, so I let things be. I didn’t tell anyone or make any travel changes, but when the Nusuk App canceled my status as a Hajj guide, I knew it was time to hang it up. I wasn’t going to Hajj this year. Nevertheless, I knew it would be good for me to visit one of my teachers instead—in my mind, if I couldn’t visit Makkah and the Prophet ﷺ in Madinah, this was the next best thing. To my surprise, some of my friends were hosting Shaykh Muhammad Haydara Al-Jilani at a summit in South America, and they allowed me to tag along.

Of course, I was disappointed, but since I never had complete confidence that I was going, my expectations for this reality were low, and I didn’t feel too impacted. Additionally, I thought being able to see Shaykh would soften the blow. Still, when a mentor started problematizing how to solve my Saudi visa issue, asking questions about what could be done, the levees of my emotional dissociation broke, and despair began to creep in. I have already exhausted all possible options.

As much as my mind tried to hide it, this momentary break highlighted some structural issues within my spiritual life. The goal post is, as Allah tells us in the Quran, “Do not lose hope in Allah’s mercy.”1 If Allah revealed this verse because some of the Prophet’s companions thought their sins would never be forgiven, what about merely things not going my way?! While I’m under no delusion to believe or claim any level of sincerity, this leads me to question what my underlying intention was from the beginning, truly to serve and earn Allah’s pleasure, or for some personal gain?

Nourishment

Immediately after boarding the plane, I noticed a familiar face. It was comforting because, despite never spending time together, I didn’t know who I would be with on this trip. Suhba (companionship) with teachers rarely occurs in a vacuum (just one-on-one with the shaykh); instead, it takes place in a shared communal experience among peers. It’s in this symbiotic exchange that we're stretched to practice what our teachers preach, because it usually cannot happen in isolation.

When we landed, two-thirds of the summit attendees did as well, and this is where I began to notice things. These brothers and sisters were chill and, dare I say, just normal. No one was being “extra,” performing all the right external signifiers of humility and in-crowd membership (i.e., special handshakes or wearing unique, culturally specific garb), and everyone was genuinely caring. Once everyone had their luggage, I noticed that people were ordering Ubers before I could. As everyone organically peeled off into the cars, a brother invited me to join him and his family so I wouldn’t have to ride alone. This sentiment prevailed throughout the entire summit.

The attendees came together with no other intention than to be in suhba with a Shaykh from the family of the Prophet ﷺ and, then, work together to come up with solutions that serve the Ummah. If anyone had something meaningful to contribute it was welcomed, regardless of age (the youngest participant was fourteen years old and the eldest was in their seventies, but young children were running around) or profession (we had Hollywood actors, professional comedians, hedge fund founders, tech entrepreneurs, tenured professors, lawyers, specialist doctors, consultants, stay-at-home moms, and Imams). It was as if sincerity was the only necessary credential..

An example of this is when, one night, Sh. Muhammad was sitting on the floor eating dinner and welcomed two brothers and me to join him. Now, Shaykh speaks English; so, when I heard one brother ask the other, “Hey, you want to get cigars tonight?” I internally shook my head, restraining a mixture of shock and laughter. These guys were so genuine that they didn't mind having this conversation right in front of Shaykh. After the other responded, “InshaAllah, let’s do it!” the first brother turned to Shaykh and asked, “Shaykh, we’re going to get cigars tonight. Is that ok?” Shaykh chuckled and responded simply with, “I don’t think so.” I thought to myself, “What a beautiful answer. He didn’t shame them or anything.” But the conversation didn’t stop there! He followed up with, “Oh shaykh! I was hoping you would give us permission, “ and the other brother said, “Shaykh, have you ever smoked before?!” And Shaykh continued smiling and simply said, “No.”

Sh. Muhammad wasn’t humoring those brothers. It was evident to everyone that he genuinely loved them. He loves everyone. It is this prophetic quality that teaches us how to love and be with others.

Every time I get to visit Sh. Muhammad, I get at least one new lesson, sometimes from him and sometimes from those around him, but always for me. I’m generally an extroverted guy and enjoy being with people, but this suhba was special. It showed me what a healthy community could look like. It doesn’t look like a group of androids, everyone reflecting the similarities of each other; rather, it is people who find a way to work together interdependently based on love and service.

Tawakkul

We had a loose schedule for the summit: one session before Dhuhr, another afterwards, and then social time from Asr until Maghrib. The sessions were a mixture of presentations from subject-matter experts on their findings and brainstorming solutions to problems. Everyone sat around the room, some on the floor, while others in chairs and on a couch, humble and passionately engaged, asking questions and sharing feedback.

The social time ended up being a passive continuation of the previous conversations, and frequently over coffee. It was riveting, but the pinnacle of our day was our time with Shaykh Muhammad. He was physically present in the home—he joked that he hadn’t left all week and had gone outside for a walk one night—and would pray and eat meals with us. However, it was after Maghrib that he would give us a khatira and field our questions.

By the second or third day, we started to notice that Shaykh’s messaging was essentially the same, centering around two things:

Keep things in perspective,

Trust in Allah

Take initiative with whatever you have.

Keep things in perspective

A sister posed a question around decision making and analysis paralysis, and Shaykh responded, “Sometimes we look at things on a big screen. Put it on a small screen.” The answer was so matter-of-fact that I didn’t appreciate its depth, initially found it comical, and struggled to restrain a giggle. He continued, “When you look at things on a big screen, things appear larger than they are. But, if you put them on a small screen, they are in perspective.”

I was dumbfounded—such a simple message, yet so comprehensive.

When we’re watching on a screen, we’re not looking at something in reality. Even if it isn’t a highly produced piece of media, the camera and lens quality alone drastically impact the final image. If we introduce professional lighting and editing, we can take the same scene, shot from the exact location, and make it unrecognizably different. Life is no different. Our perspective, what we consciously or unconsciously use as a processing filter to our experiences, directly impacts how we think and feel. After all, Allah said in a Hadith Qudsi, “I am as my servant thinks I am.”2

Trust in Allah

Now, I could have switched the order of points one and two or combined them, but I wanted to clearly define the role of perspective. That said, for Shaykh Muhammad, the two seem to be inseparable. He wasn’t just talking about the perspective we hold, but rather taking something that may initially appear overwhelming and reminding us that nothing is too great for Allah. Shaykh makes molehills out of mountains.

Ask anyone who has spent time with him, and they will tell you he is always radically optimistic. For me, Shaykh’s disposition is an embodiment of the verse where Allah says,

“And whoever is mindful of Allah, He will make a way out for them, and provide for them from sources they could never imagine. And whoever puts their trust in Allah, then He ˹alone˺ is sufficient for them. Certainly Allah achieves His Will. Allah has already set a destiny for everything.”3

The challenge to this level of trust in Allah is that it isn’t a plug-and-play solution. We cannot expect to simply spend time or read about people of this status and think we can, with the flick of a switch, uphold it ourselves. Outside of divine intervention, it requires consistent work over prolonged periods, practicing spiritual humility (intending an internal and external connectedness to God). Through perpetually striving to discover Allah’s magnificence, we are shown its direct counterdistinction in ourselves and, simultaneously, raised in status with Him.4

Take initiative with whatever you have.

A brother asked Shaykh Muhammad a question about perfectionism, and he answered, “The problem is you see yourself at the top of the mountain, but your body is still at the bottom. Just take one step.”

Even if we have correctly understood things internally, have a focused perspective, and have embodied our theology, it doesn’t exempt us from taking action. Furthermore, it doesn’t mean we should wait to act until our expectations are met. In fact, “Trying our best (i.e., striving to have Ihsan, or spiritual excellence) does not mean giving up or cowering away. It is a spiritually ethical disposition, internally and externally, the epitome of our tawakkul.”

In Perspective: A Quranic Hermeneutic of the Isra Wal-Mi'raj I said,

As we journey through our lives—souls carried by magical beasts (i.e., our bodies)—we, too, exist in a metaphorical darkness. The future is entirely unknown (to us, not Allah), and so much lies outside our control. Nevertheless, we must not be paralyzed by this; Allah commanded us, “Take action! God will see your actions.” Our responsibility is to what lies within our sphere of influence. Abdullah b. Amr b Al-Aas, a sahabi (companion) of the Prophet ﷺ, said, “Work for your life down here as if you’ll live forever, and work for the next life as if you will die tomorrow.” What lies beyond our sphere of influence we leave to God because, ultimately, from Allah we come, and to Him we shall return.

"Without suffering, you cannot reach the state of blessedness." –Rumi5

Conclusion

Hajj is a journey of submission, where we migrate from all over the world to one central location, strip ourselves of any socioeconomic signifiers to wear what is essentially two white beach towels, and follow the tradition of Prophet Ibrahim (‘alayhi salam—peace be upon him). We pray that the reward of these five days’ sacrifice is the spiritual revival of our previous sins forgiven. Although I wasn’t invited to visit the holy lands and perform Hajj this year, I was inadvertently sent on a pilgrimage of sorts. I am reminded of the verse, “Perhaps you dislike something which is good for you and like something which is bad for you. Allah knows and you do not know.” In reality, I have very little control over what I can do. Objectively good things (e.g., like serving one’s teachers or making Hajj) might not be what is best for me in the moment.

The two things that I probably speak about the most—suhba and tarbiya (spiritual nurturing)—are areas in which I learned the most on this journey, both drastically reshaped by humility. With suhba, humility reminds us that true companionship is not about ideal conditions or flawless people but about the willingness to be shaped by others, to receive counsel, and to keep showing up even when we feel unworthy or incomplete. With tarbiya, humility teaches us that knowledge and perspective mean little if they do not prompt us to take the next small, sincere step, trusting that Allah sees the effort, not just the outcome. This pilgrimage of the heart revealed to me that even when our plans are redirected, our striving is never in vain. In truth, this all boils down to humility—bowing to the reality that we have so little control, surrendering what lies beyond our reach, and taking initiative with what we have. It is through this humble submission that we trust in Allah’s wisdom, walk the path laid before us, and find our hearts revived, just as every true pilgrimage intends.

And, ultimately, with Allah is all success.

Quran 39:53.

Quran 65:2-3.

Rumi, Jalal al-Din. The Mathnawi of Jalalu’ddin Rumi. Translated and edited by Reynold A. Nicholson. 8 vols. London: Luzac & Co., 1925-1940. Vol. 4, 2003.

Sheik Muhammad is a treasure. Meet him if you can. A rare gem

Bismillah.

Jazak Allahu Khairun for the story and reflection. What is your recommendation for wearing Islamic clothes without being a false signifier of humility? On the one hand, scholars sometimes wear newspaper boy hats to show the kufi can be American in fashion, on the other hand, some scholars wear Tuniq style hats as a way to give dowah or show an alternative way to American life. Is it the Niyah? Whatever style comes truest to the heart as long as the garb is clean?

I guess my question extends to all sunnah: do we do as much as we can, no holds barred, or follow the sunnah as much as is easy, and camouflages with the customs of people around us? Thank you.