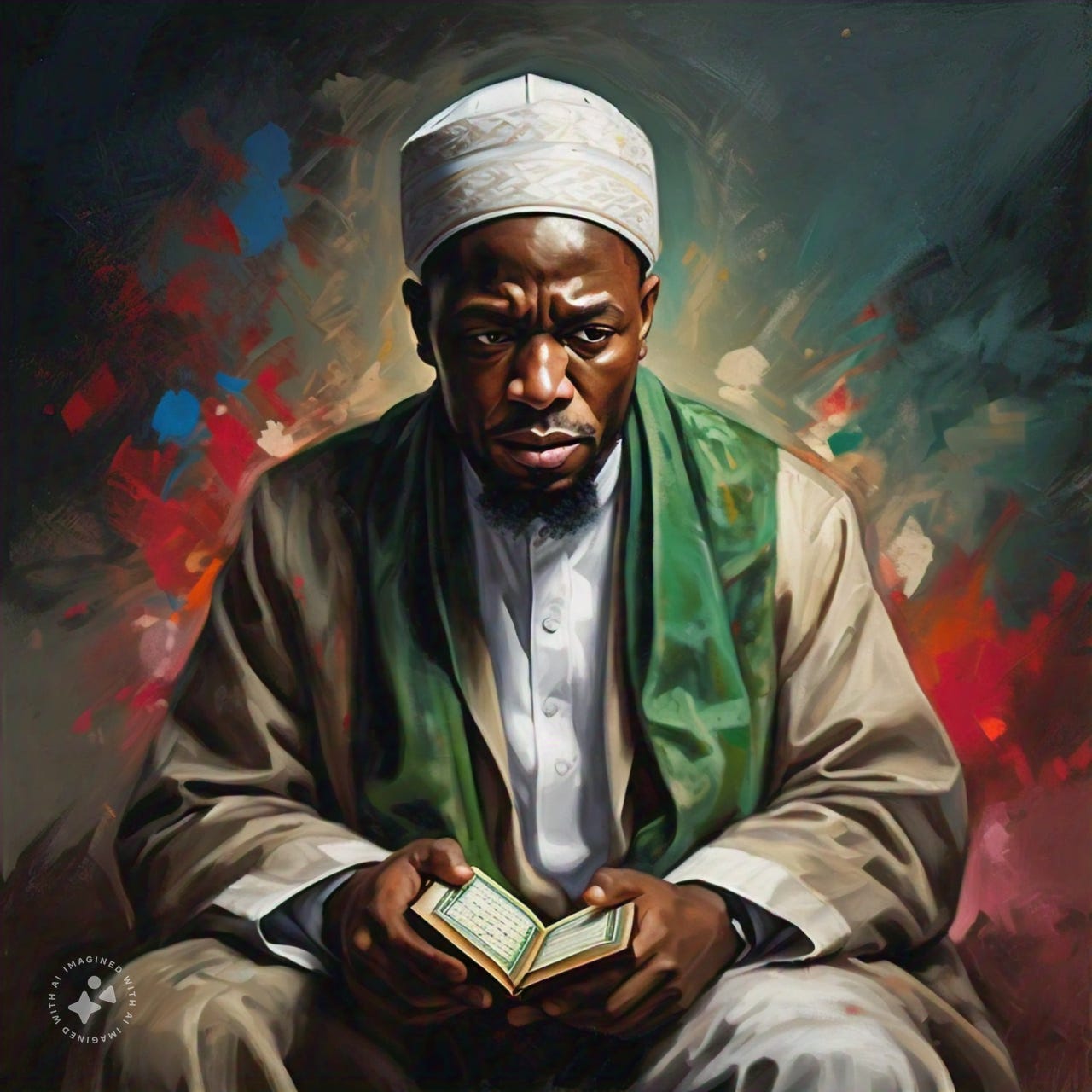

Anger + Righteous Indignation

A heart ablaze: finding purpose where frustration once ruled. Discover the journey from restless anger to steadfast spiritual resolve.

In 2011, I was twenty-one years old, studying in Saudi Arabia, and nowhere near completion. At Umm al-Qura, like many Saudi universities, foreign students must complete a two-year Arabic language intensive program before starting their college education. I delayed my college enrollment a semester for personal reasons, so I was completing my fourth academic year with at least two and a half years to go, and all my friends were graduating college. To make matters worse, I couldn’t stand the department I was enrolled in. I wasn’t jealous; I was happy for my friends but still angry.

Retrospectively thinking, I felt a mixture of frustration and self-pity wrapped in entitlement. My memory has never been particularly strong, and the Eastern educational system (built almost entirely on memorization) was challenging for me; I realized that I would be graduating later than all my friends, and both triggered my insecurities. Would I ever find happiness and stability, and did my academic challenges prove that I was dumb after all? In my mind, my life should not have been this way, and because I was young and lacking emotional intelligence, it all manifested as anger.

Young people, particularly young men, frequently complain about feeling similarly—angry with their circumstances and without an escape. However, for others, it is less about them and their future because of a moral injustice transpiring and their inability to change it. The differentiation between anger, even rage (a stronger emotion), and what philosophers call righteous indignation is very subtle. InshaAllah, this paper will explore the nuances.

“I am here loaded with chains and willing to suffer the fate that awaits me, but I tremble when I think of the fate that awaits you who would use the innocent with cruelty and oppression.”

–Nat Turner1

Anger

Dorm life in Makkah wasn’t sweet. At first, we were four bachelors living in a twenty-by-ten room of a repurposed apartment (i.e., not designed to be a dormitory) and would occasionally have guests join us, sleeping on the floor. We shared our bathroom with twelve other guys (from many different ethnicities and hygienic customs). Still, it wasn’t restricted to them—anyone from the entire apartment building could use it. At its worst, we had a roach and bedbug infestation. Al-Humdulillah (hallelujah), by 2011, the university moved the foreign students into a new dormitory. Despite still being a repurposed apartment building, it was less populated. Unfortunately, it was twenty minutes away and twice the cab fare from Masjid Al-Haram (the sacred mosque).

Life was tough; I wasn’t passionate about school, owned nothing, felt like a failure, and was past the point where it made sense to return home. I would have to return and restart my life with little to show. Mustering on was the only viable option, but that didn’t mean I enjoyed it.

Anger is an important emotion. In the Islamic spiritual paradigm, Tazkiya Al-Nafs (purifying the soul) is not to irradicate emotions or passions but to bring them into balance. IbnQuddama Al-Maqdisi mentions, “If we eradicated anger, then no one would defend themselves. … If it were not for death, we wouldn’t have the motivation to fight for God’s sake.”2 Also, in the context of legally sanctioned war, Allah describes the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and the Sahaba (Companions) as “firm with the disbelievers.”3 That firmness can only be achieved via anger, but it must have a moral compass, and, for us as Muslims, this is found in the Shariah (Islamic law). My anger was rooted in entitlement and not based on any moral principles, nor did it inspire a Taqwa (God-consciousness); therefore, it was spiritually toxic.

Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said, “The strong man is not the good wrestler, but the strong man is he who controls himself when he is angry.”4 To combat our anger, we must do the opposite: strive to remember God. There are a few things, both internal and external, we can do for this:

Remember Allah:

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “I know a phrase by repeating which the man could get rid of the angry feelings: ‘أَعُوذُ بِاللَّهِ مِنَ الشَّيْطَانِ الرَّجِيمِ (I seek refuge in Allah from the accursed devil).’”5

Change our physical position:

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “When one of you becomes angry while standing, he should sit down. If the anger leaves him, well and good; otherwise, he should lie down.”6Make Wudu (ritual ablution):

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said, “Anger comes from the devil; the devil was created of fire, and fire is extinguished only with water; so when one of you becomes angry, he should perform ablution.”7

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet depreciate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.”

–Frederick Douglass8

Righteous Indignation

I will never forget, later that year, I was probably depressed—as untreated anger can quickly turn into—and trying to cope by binge-watching Def Poetry Jam when I came across a poet named Amir Sulaiman. He was a strong bearded Black man wearing all-black Dickies, his pants above his ankles, a Kufi on his head, and performing “Danger.” I was confident he was Muslim. But the almost militant deliverance was more than his name and the warm feeling of fraternity I got from seeing a Blackamerican Muslim on this platform.

I have never been into poetry or spoken word before watching Def Poetry Jam, but their performances were mesmerizing. Amir delivered his poem, “Danger”, with a confidence and bravado that forced me to pay attention. He was angry, but his anger was starkly different than mine. While mine was confused and unfocused, his anger was sharp and poignant. Although Amir spoke about being the physical embodiment of danger, he addressed the underlying feelings that manifest it. To me, Amir Sulaiman was talking about righteous indignation.

Righteous indignation is principled and moral “anger aroused by something unjust, unworthy, or mean.”9 That’s something praiseworthy, as Prophet Muhammad ﷺ said, “He who amongst you sees something abominable should modify it with the help of his hand; and if he has not strength enough to do it, then he should do it with his tongue, and if he has not strength enough to do it, (even) then he should (abhor it) from his heart, and that is the least of faith.”10 He ﷺ wouldn’t encourage taking any action unless it were principled and righteous. Ultimately, righteous indignation is a spiritual expression of freedom because it is a rejection of complacency in the face of wrong and a stance for justice and integrity.

Describing that tension, Amir Sulaiman said,

Freedom is between the finger and the trigger

It is between the page and the pen

Between the grenade and the pin

Between righteous anger and keeping one in the chamber

So what can they do with a cat with a heart like Turner

A mind like Douglas, a mouth like Malcolm, and a voice like KRS?

For better or worse, I’m an opinionated, critical, and passionate guy; it’s tough for me to sit back and do nothing. Throughout my life, this has gotten me into trouble, sometimes with others but more frequently internally. This anger, albeit rooted in something praiseworthy, is still a burning fire. It requires ensuring the blaze does not grow to consume us, either by blinding rage or overwhelming despair. Amir vividly captures that sentiment when he says,

Justice is somewhere between reading sad poems

And 40 ounces of gasoline crashing through windows

Justice is between plans and action

Between writing letters to Congressmen and clapping the captain

“HasbnAllah wa Ni’mal Wakeel (“Allah ˹alone˺ is sufficient ˹as an aid˺ for us and ˹He˺ is the best Protector.)”11

“If you’re not ready to die for it, put the word ‘freedom’ out of your vocabulary.”

–Malcolm X12

Management

Honestly, I don’t have a solution to righteous indignation. I find myself reflecting on it, as I did in Spiritual Holding Patterns. It’s a feeling of sitting in the liminal space “between plans and action” and is not easy, especially when we are powerless to act. Nevertheless, here are some things that have helped me:

Gratitude

Sometimes, anger’s fire creates smoke that clouds our ability to see our tremendous blessings. When I was frustrated watching my friends graduate from college, as I had many years remaining, I failed to see the blessings of living in Makkah (the most sacred place in the Muslim world), my family, physical health and safety, etc. Gratitude doesn’t necessarily remove the fire of our anger, but it can provide a gentle rain to soften its flames.

“Do not lose hope in Allah’s mercy.”13

Hope, or the loss of despair (a more literal translation), is different from optimism. Dr. Cornel West said, “Optimism assumes there is enough evidence out there to warrant a reasonable conclusion that things are getting better. Hope, on the other hand, enacts the vision of a better world despite the evidence to the contrary.”14

Our hope is rooted in God, Al-’Aleem Al-Khabir (All-Knowledgable, All-Wise), and nothing else. This is a theological belief that sets an entire worldview.

This hope is not passive. We must actively strive to change the outcomes.

Make Plans

I ask myself: What can I do to alleviate the injustice I seek to remove? How can I maximize my time and effort now to better prepare myself for when I can act? Who are the people I can consult or who can support me in achieving my goal? Sitting back and smoldering never helped me much. I like to get busy!

“Teachers teach and do the world good, kings just rule and most are never understood.”

–KRS-One15

In the end, Allah’s plan unfolded with wisdom and mercy. Later that same year, I was blessed to get married and move out of the dorms. Although it took nearly a decade, I eventually completed my studies and graduated, Al-Humdulillah. Reflecting on those early, solitary days in Makkah, I feel a deep sense of pity for the younger version of myself. I spent so much time and energy frustrated over challenges I had willingly chosen by embarking on this journey. No one had compelled me to study abroad, yet I allowed my anger to overshadow that truth. Looking back, I realize that if I had approached these struggles with greater self-discipline and resilience, I could have achieved even more during those formative years.

However, had I not been angry, I might never have found the insight to write this post. That youthful anger, misguided as it was, became a teacher in its own way. It helped me recognize the distinction between self-centered frustration and righteous indignation, showing me that true strength lies not in eradicating our emotions but in refining and directing them for a higher purpose. Today, I still get angry and indignant. I try to carry the lessons of my previous experiences forward with gratitude and hope, knowing that even in our darkest moments, there is wisdom to be gleaned and a path to growth.

May Allah guide us all to use our emotions as tools for good, to recognize His wisdom in every hardship, and to transform our challenges into stepping stones toward a more purposeful life. Ameen.

Ultimately, with Allah is all success.

Gray, Thomas R. The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southampton, Virginia. Baltimore: Lucas and Deaver, 1831.

IbnQudama Al-Maqdisi. Ahmad b. Abdul-Rahman. Mukhtasr Minhaj Al-Qasidin. Damascus, Syria: Maktabah Dar Al-Bayan, 1978. 152-153.

Quran 48:29.

Douglass, Frederick. “West India Emancipation” Speech, Canandaigua, NY, August 3, 1857. In The Life and Writings of Frederick Douglass, edited by Philip S. Foner, Vol. 2, 437-438. New York: International Publishers, 1950.

Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “indignation,” accessed November 11, 2024, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/indignation.

Quran 3:173.

Malcolm X. The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley. New York: Ballantine Books, 1992, 378.

Quran 39:53.

West, Cornel. Race Matters. Boston: Beacon Press, 1993. 73.

KRS-One, “My Philosophy,” By All Means Necessary, Jive Records, 1988.

Jzk Allah Khair mawlana… I’ve been thinking about this for a bit to the extent that I’ve subscribed to meditation apps alongside trying to hone my time on the prayer mat to be present and as calm as possible, and came across the prophetic guidance Subhan Allah of laying down when angry.. I’ve been trying to understand where the modern science-backed spirituality and meditation exercises intersect with our faith, and this is an enlightening example of using posture to self-regulate.. May Allah increase our fahm & ilm..